The illegal entry of an estimated 6 to 10 million aliens (the legal term according to immigration law and statutes) to the United States in the past four years has been a subject of significant debate and concern. From known encounters to “got-aways,” the actual number may remain unknown. From illegal entries between ports of entry to the dubious utilization of the immigration parole process via new governmental cellphone applications through ports of entry, the border control and immigration infrastructure has been abused and overwhelmed. The impact has been immediate and will also be long-lasting on many fronts.

This recent unique change in national immigration policy creating the increase is primarily a political issue, but it has significant follow-on societal, fiscal, and economic consequences. An influx of immigrants will likely continue, and possibly increase, until a change of enforcement policy. Should there be a return to the enforcement of the current federal statutes and regulations on the books, there may be a shock to the current system or expectations and the plans of millions of aliens currently residing in the United States.

To evade arrest, detention, and deportation or removal, recent aliens are likely to join over 10 million other aliens of varying status already in the country in seeking additional or alternative methods to remain within the United States. U visas offer an easier way to exploit and buy time than other avenues. One method immigrants may exploit is discussed in a 2018 Domestic Preparedness article (U Visas – A Hidden Homeland Security Vulnerability) involving the U nonimmigrant status (U visa) application process. The article stressed that the U visa process was a hidden homeland vulnerability not fully understood or overseen. This important process remains a serious risk for abuse to provide a defense against the timely and fair enforcement of immigration laws.

U Visa Application Process

A brief review of the previous article would explain the process and concerns more fully. As a short reminder, the U visa is reserved for “victims of certain crimes who have suffered mental or physical abuse and are helpful to law enforcement or government officials in the investigation or prosecution of criminal activity.” The U visa is different from the T visa for victims of human trafficking – another concern with the increase in smuggled people.

The Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 created the U visa. The new visa was to strengthen law enforcement agencies’ ability to investigate and prosecute cases of domestic violence, sexual assault, trafficking of aliens, and other crimes. This visa offers protection to crime victims who have suffered substantial mental or physical abuse and are willing to help authorities in the investigation or prosecution of that criminal activity.

With an annual limit of 10,000 visas a year for principal petitioners, the U visa is valid for four years and eligible for extensions if another immigration adjustment or status is not granted. The approved applicant (petitioner) is eligible to apply for a legal permanent resident card (or green card) after three years providing a possibly easier pathway to United States citizenship than other avenues. Making the U visa even more valuable, there is no limit for petitioner family members deriving status from the applicant or petitioner. Those on the waiting list for review for a visa are granted deferred action or parole and eligible for work authorization by virtue of this status. It is a strong shield within the immigration process to remain in the United States – especially for those not eligible for other options.

U Visa Statistics

The Congressional Research Service reported in 2023 that the U visas process took approximately five years for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to adjudicate an application. If the application is approved, the petitioner is placed on a waiting list and granted parole or deferred action. Due to the current backlog, it can reportedly take up to 17 more years to receive U visa status because of the 10,000 annual cap. The petitioner is permitted to remain and work within the United States during this extended process.

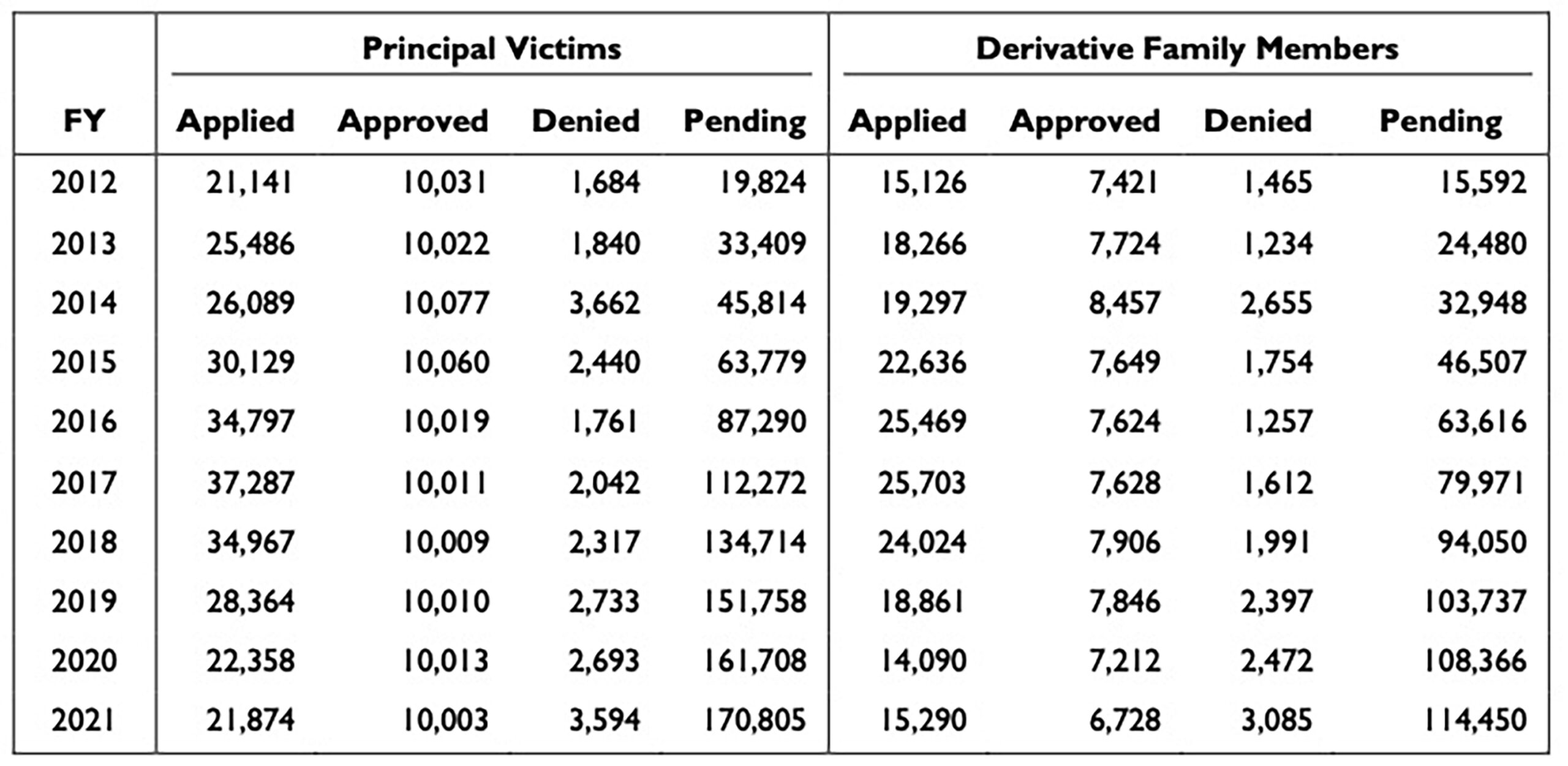

The Congressional Research Service received the FY2012-2021 U visa statistics in Table 1 from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). As of the time of the reporting, over 285,000 pending petitioners had legal status to remain in the United States. According to the report:

While the number of individuals who can receive U status is limited to 10,000 principal petitioners each fiscal year, there is no limit on the number of individuals with U status (whether principal or derivative petitioners) who can subsequently adjust to [legal permanent resident] status in a given fiscal year.

Petitioner Arrest Histories

In response to concerns regarding potential integrity issues and fraud involving the process, USCIS provided in 2020 an analysis of U visa petitioner arrest data between fiscal years 2012 and 2018. The analysis found that 34.7% of the principal petitioners and 17.5% of derivative petitioners “had a previous arrest or apprehension for a criminal offense or an immigration-related civil offense.” The most common arrests were reportedly for immigration offenses and traffic violations. The report concluded:

This comprehensive research on key demographic and filing trends will support USCIS in developing data-driven regulatory and policy changes in order to improve the integrity of the U visa program, ensure that the program is following congressional intent, and increase efficiency in processing U visa petitions. By considering these findings when developing policy and regulatory changes, USCIS can reduce frivolous filings, rectify program vulnerabilities, and increase benefit integrity – key components of USCIS’ mission.

The arrest history of valid petitioners may be a homeland security or public safety concern for discussion. However, the abuse of the process by petitioners who were not crime victims or witnesses could be a much larger homeland security threat. It floods the system with fraudulent claims that harm actual victims for which the nonimmigrant status was created to benefit.

Recent Prosecutions

Some federal prosecutions have demonstrated an abuse of the process to evade deportation and other immigration procedures:

- Six subjects were indicted in Illinois in 2024 for conspiring to stage armed robberies to obtain U visas.

- Two New York subjects were indicted in Massachusetts in 2024 for the same immigration fraud charges.

- A subject was convicted in Pennsylvania in 2023 for visa fraud and conspiracy.

- Two were sentenced to prison in 2019 in South Carolina for staging an armed robbery.

- Two more were indicted in Virginia in 2019 for a staged robbery.

Fictitious criminal activity and reporting can have serious consequences. For example, a 2024 staged armed robbery at a Texas gas station resulted in a fatal shooting. The performed crime was conducted to support a fraudulent future U visa claim and insurance fraud. An uninvolved witness reacted to the staged robbery and fatally shot the purported armed robber in the parking lot.

The number of prosecutions is likely lower than the amount of fraud within the process. As discussed in the 2018 article, there were numerous weaknesses and failures in the application and review process to identify fraudulent applications. This important immigration process remains a serious risk for abuse to provide defense against the timely and fair enforcement of immigration laws.

Worst-Case Scenario

Well beyond impeding victims’ rightful claims, there is a worst-case scenario. With hundreds of intercepted border crossers on terrorist watch lists, open-door border policies pose national and homeland security threats. It is likely that state and non-state actors are hiding within large groups that are illegally entering the United States. Serious security threats are more likely to pay cartel smugglers to include them in the separate “got-away” groups that cross the border after the zone is flooded in a nearby area with families for time-consuming processing.

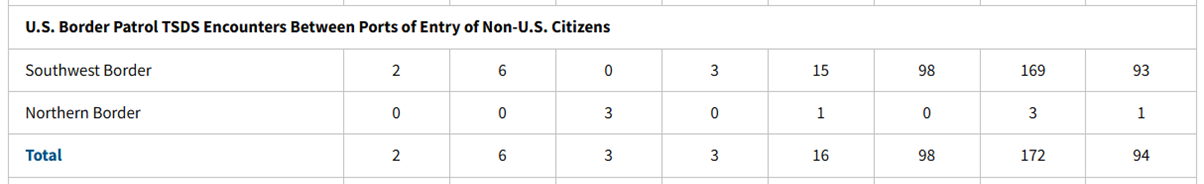

U.S. Customs and Border Protection terrorist screening data set encounters between the ports of entry demonstrates a trend in the wrong direction. Below are the reported numbers from fiscal years 2017 to 2024 (as of July 15, 2024).

Despite being an imminent threat, a state or non-state actor could use the U visa process as a shield to remain in the United States with a protective status for many years, if not decades. This is a worst-case scenario with possible worst-case consequences. It could become yet another failure to connect the dots prior to the next serious national or homeland security incident.

Continued Vulnerability

It remains critical for Congress to ensure that this vital and worthwhile immigration program is properly overseen and not exploited by individuals or criminal or terrorist organizations. Congress could utilize the Congressional Research Service, Government Accountability Office, congressional hearings, and other avenues to routinely review and evaluate the execution of the U visa process. DHS Office of Inspector General could also play an essential oversight and inspection role.

With the addition of millions of aliens into the United States in the last four years with limited or no background investigation, the national and homeland security threats have greatly expanded. If there is a return to previous immigration enforcement at the border and adherence to current statutes and regulations with a new administration or policy modification, millions of aliens shall be subject to arrest, detention, and deportation or removal. To evade these consequences and buy time, some aliens may exploit the U visa process to remain in the country and bypass the current legal consequences for years or decades.

As stressed in the 2018 article, it would be wise to understand and address these hidden vulnerabilities before they become the topic of the 24-hour news cycle and numerous congressional hearings that would threaten or overly restrict the U visa program. Enhanced attention, comprehensive training, and robust oversight could help avoid a catastrophe. Unfortunately, it often takes a major crisis or tragedy for oversight and change to be considered. This is another opportunity to react and prepare rather than fail and repair.

Robert C. Hutchinson

Robert C. Hutchinson, a long-time contributor to Domestic Preparedness, was a former police chief and deputy special agent in charge with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Homeland Security Investigations in Miami, Florida. He retired after more than 28 years as a special agent with DHS and the legacy U.S. Customs Service. He was previously the deputy director for the agency’s national emergency preparedness division and assistant director for its national firearms and tactical training division. His over 40 writings and presentations often address the important need for cooperation, coordination and collaboration between the fields of public health, emergency management and law enforcement, especially in the area of pandemic preparedness. He received his graduate degrees at the University of Delaware in public administration and Naval Postgraduate School in homeland security studies. He currently serves on the Domestic Preparedness Advisory Board.

- Robert C. Hutchinsonhttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/robert-c-hutchinson

- Robert C. Hutchinsonhttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/robert-c-hutchinson

- Robert C. Hutchinsonhttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/robert-c-hutchinson

- Robert C. Hutchinsonhttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/robert-c-hutchinson