- Articles, Emergency Management, Law Enforcement, Military, Science & Technology

- Adam Tager

Emergency managers are project managers. While the intersection between the two professions is not often explicitly highlighted, navigating the phases of emergency management largely follows the project management framework. Therefore, a deeper understanding of project management best practices can only serve to enhance the ability to help communities and execute no-fail missions.

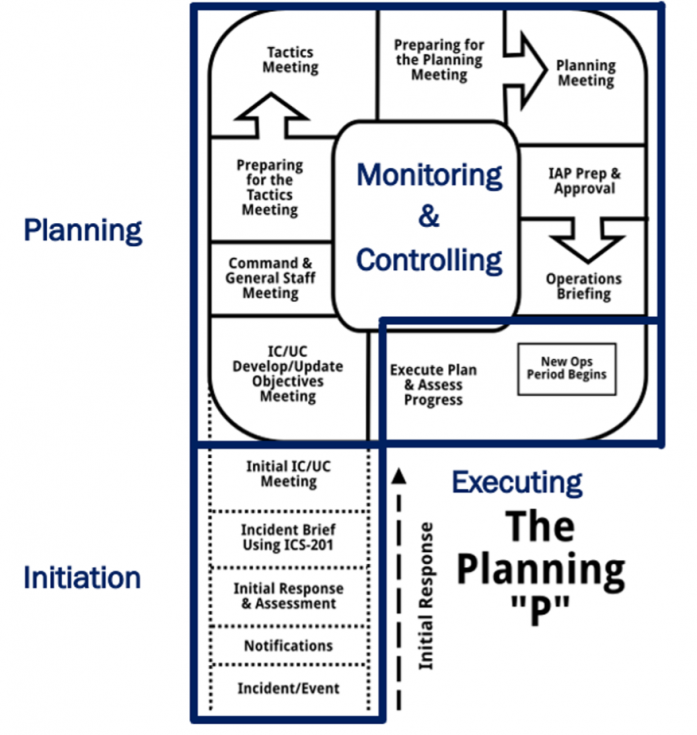

According to the Project Management Institute (PMI), a leading professional organization for project managers, a project is defined as “a temporary effort to create value through a unique product, service or result,” while project management is “the use of specific knowledge, skills, tools and techniques to deliver something of value to people.” Using these definitions, projects in emergency management can include a wide range of actions such as the development of an incident action plan (IAP) (see Figure 1), the creation of a response framework, the establishment of a technical team, or the design and execution of a training exercise. For this article, the example of designing and conducting a training exercise is used as a consistent theme throughout.

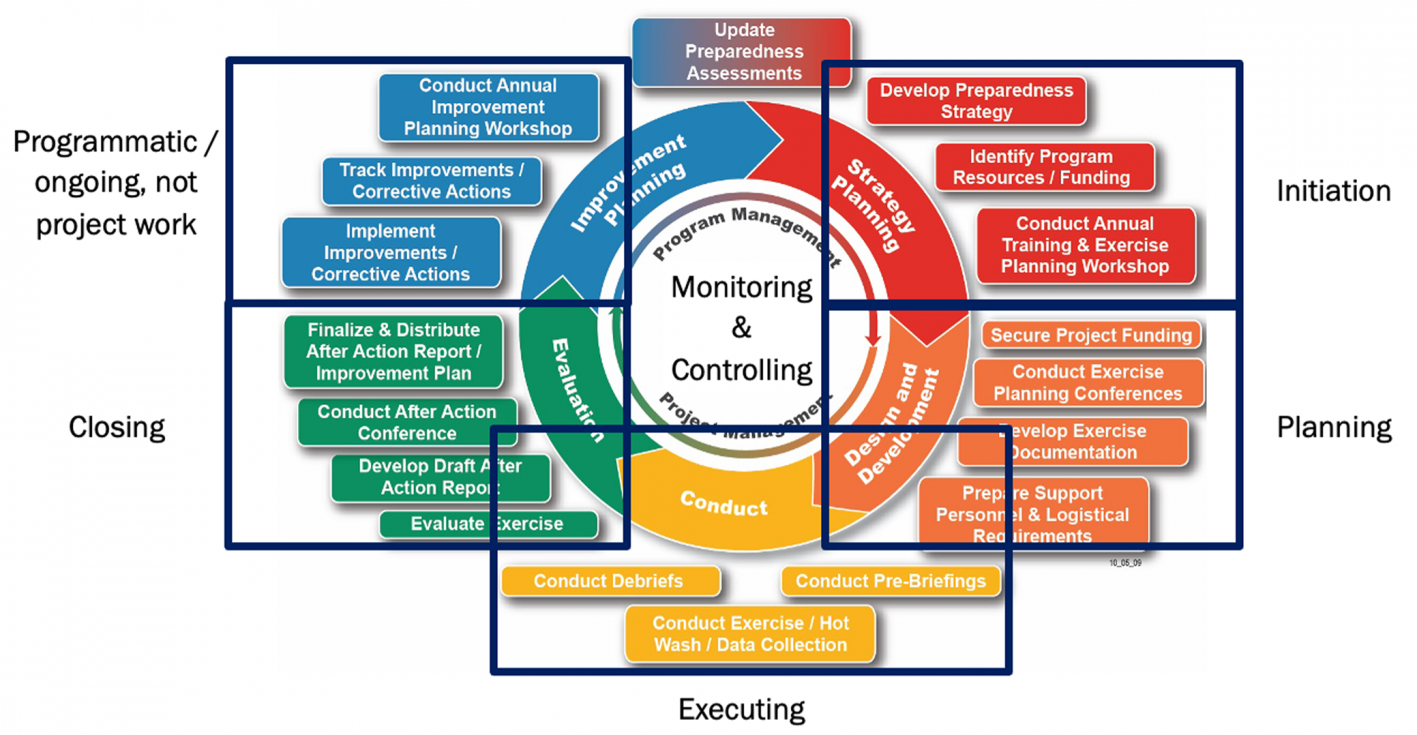

Although it uses different terms, the Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program (HSEEP) utilizes a standard project management methodology that breaks the process down into five phases. Specifically, the phases of project management overlap with the phases of HSEEP, just using different terminology (see Figure 2). The phases of project management include initiating (strategy planning), planning (design and development), executing (conduct), monitoring and controlling (throughout all phases), and closing (evaluation).

Initiating

The initiating action is self-evident during response operations when the incident starts with a defined event – sometimes referred to as boom, landfall, or T-0. However, during all other phases of emergency management, initiating a project is an intentional action. In the public sector, initiation can be precipitated by a number of factors, including legal requirements or organizational needs, and is typically championed by a senior elected or career official. This official becomes the project sponsor and can help provide top cover to acquire resources when necessary and/or undertake other actions to help ensure project success. The sponsor may be ultimately responsible for project outcomes but is typically not at the working level and should not be the same as the project manager, if possible.

Therefore, it is incumbent upon the project manager to understand the purpose of project initiation and the expectations of the project sponsor for the project to be viewed as successful. This information can be put into a project charter that serves as a foundational document creating a shared understanding of high-level project purpose and outcomes. However, unless the project is very large in scope, it is possible to combine the project charter document with the more comprehensive project plan. This may also be applicable in emergency management when time plays a crucial factor.

In the example of HSEEP, the sponsor will likely communicate the policy that should be exercised, the scenario that should be used, and/or the type of exercise, while the program manager carries out the tactical execution of that goal. Although not a perfect comparison, in the example of the ubiquitous “Planning P,” initiation is typically the tail that involves initial assessments and briefings (see Figure 1).

Planning

After the project is initiated, the planning process begins. During the planning process, several key questions should be answered:

What has to be done? (Type of exercise, scenario, policy to validate, etc.)

When will it be done? (Deadlines, timelines, etc.)

What is needed to do it? (Materials, contract support, facilities, vehicles, etc.)

How much will it cost? (Budget)

Who needs to be informed? (Stakeholders and information needs)

The answers to these questions become the foundation of a project management plan (PMP) – a comprehensive, tactical-level document that guides the project through completion. The initial PMP can expand or contract to meet the project scope and needs, but typically includes sections or appendices discussing known assumptions, initial schedule and budget, known and anticipated risks, stakeholders and communications plan, and change management procedures.

The project management phases – initiating, planning, executing, monitoring and controlling, and closing – can be used to design and conduct training exercises.

The PMP should also outline the project approach or the method for how the work is going to be completed. There are a wide variety of project approaches that suit different project types and project management preferences, but four of the most common are described here.

Predictive (or Waterfall) Approach: This type of project approach flows from one phase to the other, implying that one phase finishes before the next begins. This end-to-beginning relationship between phases gives it a waterfall appearance. Predictive is one of the most common approaches and works best when the scope of the project is well-defined and relatively stable. Any changes part way through the project, such as changing the scenario in the exercise, can be very expensive and time-consuming. The waterfall approach is common for exercise development but may not be the best option.

Incremental Approach: This approach allows for multiple deliverables to be developed simultaneously, with the final deliverable being complete once they are all integrated. This can reduce the development time, but it requires a lot of communication and integration to make sure everything works together in the end. The incremental approach may be well suited for exercise development, as it allows more flexibility for working groups to meet in tandem, negotiations for location occurring as materials are being developed, etc.

Iterative Approach: This approach adds features and functionality through multiple development cycles throughout the project lifecycle. This may be effective for an exercise series but likely not for a single exercise.

Agile Approach: This approach, which is popular in software development, is gaining prominence. It is dynamic and allows stakeholders to prioritize their requirements frequently to direct work and adapt them as the project progresses. Although typically not appropriate for exercise design, an agile-like approach may be used when prioritizing, planning, and executing different objectives across multiple operational periods during response operations.

The information in the initial PMP will be baselines or best educated guesses. The budget, timeline, assumptions, stakeholders, and other factors can, and typically do, change through the project life due to new information. It is expected that these will continue to be refined during project execution through a process called progressive elaboration. Due to this, it is essential to have a clear change management plan set in the initial PMP and for all changes to be documented in a changelog.

Another aspect to consider during planning is the project stakeholders. Knowing the stakeholders allows the project manager to determine who needs to be informed of what, when, how, and by whom. Keeping this information in a stakeholder register in the form of a Responsibility Assignment Matrix (RAM) can be a good reference and including it in the project plan allows those stakeholders to concur on the information they are receiving. An example RAM for a training exercise is shown in Figure 3.

Stakeholder | Info Needs | Medium | Frequency | Owner |

Senior Officials | Project Status | Written report | Monthly | Project Manager |

Project Sponsor | Project Updates | Meeting | Weekly | Project Manager |

Project Manager | Status | Meetings | Daily | Project Team |

Working Group Members | Status | Phone call | Weekly | Project Manager |

Core Planning Team | Project Updates | Meeting | Daily | Project Manager |

Fig. 3. Example of a Responsibility Assignment Matrix (RAM) (Source: Tager, 2022).

Finally, all projects have opportunities and risks, so it is important to identify and plan for them. Response plans typically include the set actions that can be taken when a threat or opportunity is encountered (see Figure 4). The actions can also be used to help decide how to respond to an unanticipated risk or opportunity discovered during project execution.

Individual Project Threats | Individual Project Opportunities | Overall Project Risk |

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Potential responses to threats and opportunities based on information from PMI’s (2017) guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK guide) (Source: Tager, 2022).

Executing

When planning is complete, the project moves into the execution phase. The execution of training exercises is typically more abridged than the execution of other large projects, as exercise conduct does not typically extend more than a few days or a week. However, regardless of the timeframe for project execution or exercise conduct, a big part of project execution is ensuring quality, ensuring progress, and managing change. As the project progresses, in addition to managing change, it is necessary to analyze project progress and status, identify variances, and communicate that to relevant stakeholders as identified on the RAM. For example, if exercise play goes in a different direction than anticipated, it is important to recognize this deviance and react, typically by steering players back to the desired path or utilizing different injects during exercise play.

Monitoring and Controlling

Throughout all phases of the project, it is important to be constantly monitoring project progress and controlling actions. For example, it should be noted if planning steps are taking too long, and the project manager should control for that by altering the schedule or activities. Similarly, during the execution phase or conduct of an exercise, consider updating the materials if there are many questions in the pre-brief, ensure that the scenario injects are appropriate for the extent of play, review progress against the expected timeline, etc. While monitoring and controlling are designated as an independent project phase by PMI, they should be ongoing throughout all other project phases as well.

Initiating

The initiating action is self-evident during response operations when the incident starts with a defined event – sometimes referred to as boom, landfall, or T-0. However, during all other phases of emergency management, initiating a project is an intentional action. In the public sector, initiation can be precipitated by a number of factors, including legal requirements or organizational needs, and is typically championed by a senior elected or career official. This official becomes the project sponsor and can help provide top cover to acquire resources when necessary and/or undertake other actions to help ensure project success. The sponsor may be ultimately responsible for project outcomes but is typically not at the working level and should not be the same as the project manager, if possible.

Therefore, it is incumbent upon the project manager to understand the purpose of project initiation and the expectations of the project sponsor for the project to be viewed as successful. This information can be put into a project charter that serves as a foundational document creating a shared understanding of high-level project purpose and outcomes. However, unless the project is very large in scope, it is possible to combine the project charter document with the more comprehensive project plan. This may also be applicable in emergency management when time plays a crucial factor.

In the example of HSEEP, the sponsor will likely communicate the policy that should be exercised, the scenario that should be used, and/or the type of exercise, while the program manager carries out the tactical execution of that goal. Although not a perfect comparison, in the example of the ubiquitous “Planning P,” initiation is typically the tail that involves initial assessments and briefings (see Figure 1).

Planning

After the project is initiated, the planning process begins. During the planning process, several key questions should be answered:

What has to be done? (Type of exercise, scenario, policy to validate, etc.)

When will it be done? (Deadlines, timelines, etc.)

What is needed to do it? (Materials, contract support, facilities, vehicles, etc.)

How much will it cost? (Budget)

Who needs to be informed? (Stakeholders and information needs)

The answers to these questions become the foundation of a project management plan (PMP) – a comprehensive, tactical-level document that guides the project through completion. The initial PMP can expand or contract to meet the project scope and needs, but typically includes sections or appendices discussing known assumptions, initial schedule and budget, known and anticipated risks, stakeholders and communications plan, and change management procedures.

The project management phases – initiating, planning, executing, monitoring and controlling, and closing – can be used to design and conduct training exercises.

The PMP should also outline the project approach or the method for how the work is going to be completed. There are a wide variety of project approaches that suit different project types and project management preferences, but four of the most common are described here.

Predictive (or Waterfall) Approach: This type of project approach flows from one phase to the other, implying that one phase finishes before the next begins. This end-to-beginning relationship between phases gives it a waterfall appearance. Predictive is one of the most common approaches and works best when the scope of the project is well-defined and relatively stable. Any changes part way through the project, such as changing the scenario in the exercise, can be very expensive and time-consuming. The waterfall approach is common for exercise development but may not be the best option.

Incremental Approach: This approach allows for multiple deliverables to be developed simultaneously, with the final deliverable being complete once they are all integrated. This can reduce the development time, but it requires a lot of communication and integration to make sure everything works together in the end. The incremental approach may be well suited for exercise development, as it allows more flexibility for working groups to meet in tandem, negotiations for location occurring as materials are being developed, etc.

Iterative Approach: This approach adds features and functionality through multiple development cycles throughout the project lifecycle. This may be effective for an exercise series but likely not for a single exercise.

Agile Approach: This approach, which is popular in software development, is gaining prominence. It is dynamic and allows stakeholders to prioritize their requirements frequently to direct work and adapt them as the project progresses. Although typically not appropriate for exercise design, an agile-like approach may be used when prioritizing, planning, and executing different objectives across multiple operational periods during response operations.

The information in the initial PMP will be baselines or best educated guesses. The budget, timeline, assumptions, stakeholders, and other factors can, and typically do, change through the project life due to new information. It is expected that these will continue to be refined during project execution through a process called progressive elaboration. Due to this, it is essential to have a clear change management plan set in the initial PMP and for all changes to be documented in a changelog.

Another aspect to consider during planning is the project stakeholders. Knowing the stakeholders allows the project manager to determine who needs to be informed of what, when, how, and by whom. Keeping this information in a stakeholder register in the form of a Responsibility Assignment Matrix (RAM) can be a good reference and including it in the project plan allows those stakeholders to concur on the information they are receiving. An example RAM for a training exercise is shown in Figure 3.

Stakeholder | Info Needs | Medium | Frequency | Owner |

Senior Officials | Project Status | Written report | Monthly | Project Manager |

Project Sponsor | Project Updates | Meeting | Weekly | Project Manager |

Project Manager | Status | Meetings | Daily | Project Team |

Working Group Members | Status | Phone call | Weekly | Project Manager |

Core Planning Team | Project Updates | Meeting | Daily | Project Manager |

Fig. 3. Example of a Responsibility Assignment Matrix (RAM) (Source: Tager, 2022).

Finally, all projects have opportunities and risks, so it is important to identify and plan for them. Response plans typically include the set actions that can be taken when a threat or opportunity is encountered (see Figure 4). The actions can also be used to help decide how to respond to an unanticipated risk or opportunity discovered during project execution.

Individual Project Threats | Individual Project Opportunities | Overall Project Risk |

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Potential responses to threats and opportunities based on information from PMI’s (2017) guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK guide) (Source: Tager, 2022).

Executing

When planning is complete, the project moves into the execution phase. The execution of training exercises is typically more abridged than the execution of other large projects, as exercise conduct does not typically extend more than a few days or a week. However, regardless of the timeframe for project execution or exercise conduct, a big part of project execution is ensuring quality, ensuring progress, and managing change. As the project progresses, in addition to managing change, it is necessary to analyze project progress and status, identify variances, and communicate that to relevant stakeholders as identified on the RAM. For example, if exercise play goes in a different direction than anticipated, it is important to recognize this deviance and react, typically by steering players back to the desired path or utilizing different injects during exercise play.

Monitoring and Controlling

Throughout all phases of the project, it is important to be constantly monitoring project progress and controlling actions. For example, it should be noted if planning steps are taking too long, and the project manager should control for that by altering the schedule or activities. Similarly, during the execution phase or conduct of an exercise, consider updating the materials if there are many questions in the pre-brief, ensure that the scenario injects are appropriate for the extent of play, review progress against the expected timeline, etc. While monitoring and controlling are designated as an independent project phase by PMI, they should be ongoing throughout all other project phases as well.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of FEMA or the U.S. government.

Adam Tager

Adam Tager, M.S., CEM, PMP, serves as the Disaster Readiness Program Manager in the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Mission Support Executive Office. In this role, he leads readiness and response efforts on behalf of the Associate Administrator for Mission Support. Previous to this, he served as a field operations analyst and a consultant supporting FEMA and the Department of Defense. He has worked with national and state emergency management programs and has had roles in all-hazards event response and recovery, the development and conduct of training exercises, and the development and writing of after-action reports.

- Adam Tagerhttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/adam-tager