Exercises play a vital role in preparing organizations to respond to critical incidents and have been used by the U.S. government for decades to enhance department and agency understanding of their respective roles and responsibilities and to help prepare for terrorist threats. Although organizations can develop plans, expand their resources, and add personnel with expertise in responding to different threats and hazards, the planning process cannot move beyond the theoretical if exercises do not validate plans. Having the right equipment and personnel to respond to a critical incident may provide insight into what an organization’s response capabilities can accomplish. Still, unless those capabilities are tested in exercises as part of a comprehensive and integrated preparedness program, the organization cannot answer the fundamental question that its leadership needs to know: Can the organization effectively respond when a threat or hazard arises?

Currently Used Exercise Tools

During operations-based exercises, participants execute functions in a simulated environment to recreate what would happen if the scenario were real. Operations-based exercises, which include drills and full-scale exercises, are easily evaluated with quantitative assessment tools (e.g., whether participants set up a command post, initiate communications, or employ personnel and resources within a specific time). However, rather than demonstrating capabilities, participants in discussion-based exercises such as tabletop exercises (TTX) talk through a response policy, plan, or procedure and discuss what they would be doing. As a result, TTXs do not readily lend themselves to quantitative assessments, nor is there an industry standard for evaluating their effectiveness.

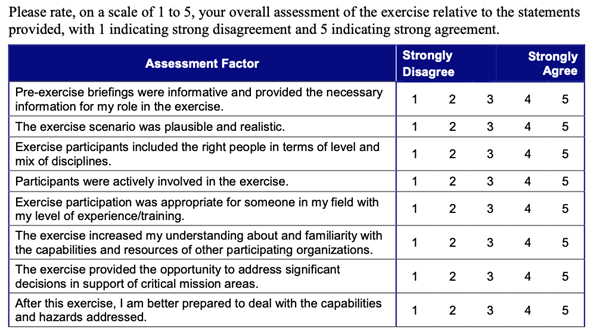

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), through its Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program (HSEEP), has taken essential steps to improve the evaluation of exercises. Beginning nearly a decade ago, FEMA published a sample Participant Feedback Form – HSEEP-C09, which organizations can adapt. In this sample form, FEMA recommended that organizations solicit opinions from exercise participants on eight statements using a Likert scale, including whether participants observed strengths during the exercise or areas that needed improvement. These statements, however, only solicited general assessments about preparedness, and the feedback was not directly tied to exercise objectives. In January 2020, FEMA updated the HSEEP guide, but has not updated the Participant Feedback Form. Therefore, the current HSEEP exercise evaluation methodology may not solicit sufficient data to assist organizations in accurately measuring a TTX’s overall effectiveness in improving organizational preparedness.

Designing and Evaluating Tabletop Exercises

TTXs provide a forum for participants to discuss policies, procedures, or plans that relate to how the organization will respond to a critical incident. During TTXs, facilitators or moderators lead the discussion to keep participants moving toward meeting the exercise objectives. The exercises must have realistic scenarios to accurately assess response capabilities. They should be well-designed, take into account how adults learn best, and engage participants in ways that build better muscle memory and avoid negative training; that is, training that reinforces responses that are not aligned with an organization’s policies and procedures, and obstruct or otherwise interfere with future learning. Post-incident analyses repeatedly demonstrate that experience gained during exercises is one of the best ways “to prepare teams to respond effectively to an emergency.”

After the exercise, it is important to find the best way to evaluate whether the TTX has increased the participants’ short-term and long-term knowledge or behaviors and to determine whether the exercise improved organizational preparedness. Researchers and academic scholars have examined different evaluation methodologies. For example, in 2017, nine researchers conducted an extensive study of whether a TTX enhanced the pediatric emergency preparedness of 26 pediatricians and public health practitioners from four states. After analyzing the data, the researchers published their study in 2019 and concluded that TTXs “increased emergency preparedness knowledge and confidence.”

Using the wrong evaluation methodology, organizations may not be able to accurately determine whether they are getting a high return on their training investments. However, since a TTX can be conducted cost-effectively in a short time, the method used to evaluate their effectiveness must also be capable of being completed relatively quickly and cost-effectively.

Quantitative Assessments

The driving principle behind exercise evaluation should be “to determine whether exercise objectives were met and to identify opportunities for program improvement.” The HSEEP’s Participant Feedback Form’s quantitative measurements are limited and primarily focused on exercise delivery and asking participants to provide general and conclusory statements about whether the exercise improved their preparedness (see Fig. 1).

The numerical scores that can be aggregated in the HSEEP statements have utility, but will not produce sufficient quantitative data because the questions are limited, are not tied explicitly to exercise objectives, and do not assign different weight values to the answers. Using objective-based and goal-based criteria can help distinguish between evaluative statements focused on exercise delivery and those focused on whether the TTX met a particular objective. Assigning a weighted numerical value for each response is also critical. For example, responses focused on exercise design and delivery should not be weighted as heavily as those focused on how well the TTX met a particular objective and improved the organization’s preparedness. In addition, when scores are averaged and compared over time, they produce a more accurate evaluation of whether the TTX improved the organization’s preparedness.

The following types of statements can be adapted by organizations to their specific TTX. Scoring these exercise factors and assigning them a weighted value creates what the authors call an XF Score.

Please rate, on a scale of 1 to 5, your response to the following statements, with 1 indicating that you strongly disagree, a 2 indicating that you disagree, a 3 indicating that you are undecided or neutral, a 4 indicating that you agree, and a 5 indicating that you strongly agree.

- The TTX improved my understanding of my organization’s critical incident response capabilities [to the specific scenario being tested] (multiply this response by 2);

- The TTX improved my understanding of other organization’s response capabilities, plans, policies, and procedures and how they integrate with my organization’s critical incident response plans, policies, and procedures (multiply this response by 2);

- TTX objective 1 was to … [repeat for each objective] was aligned with assessing my organization’s preparedness to respond to this type of critical incident (multiply this response by 3). (This should be the main TTX objective.);

- TTX objective 2 was to … [repeat for each objective] was met (multiply this response by 3);

- The TTX revealed a gap in my organization’s critical incident response capabilities, plans, policies, and procedures (multiply this response by 2);

- The TTX revealed areas where my organization can improve its preparedness to respond to this or other critical incidents (multiply this response by 2);

- As a result of the TTX, I or my organization will be changing the way that I or we respond to critical incidents (multiply this response by 3). (This helps to measure behavioral change.); and

- As a result of the TTX, my organization has improved its ability to respond to this type of incident (multiply this response by 2).

Participant responses that are anonymous tend to produce more reliable quantitative data to analyze objectively. In addition, a scoring system that assigns the highest value to questions aligning with exercise objectives and goals (e.g., tasks and issues with the greatest importance to the organization’s preparedness), and a scoring system that assigns the lowest value to exercise delivery, would produce more meaningful results about the exercise’s effectiveness than HSEEP’s Participant Feedback Form. For example, median score increases over time could be used to measure the degree to which the TTX transferred learning to participants and participants changed their behavior.

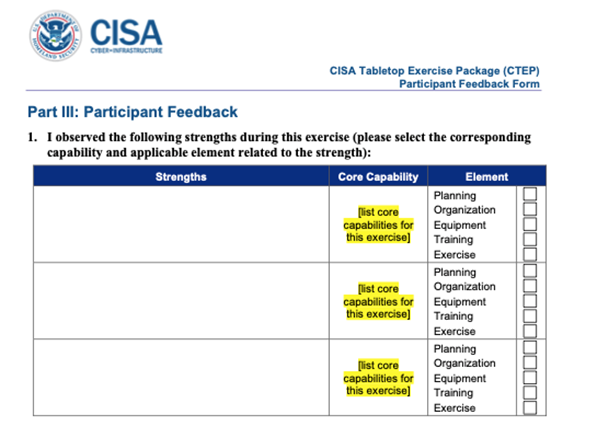

Organizations, however, must avoid exclusive reliance on quantitative assessments. For example, HSSEP’s Participant Feedback Form does include qualitative information, which provides some degree of categorization for the information sought regarding core capabilities. However, that qualitative data does not appear to be tied to exercise objectives, as the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency (CISA) illustrates in its use of HSEEP’s form (see Fig. 2).

Integrating Quantitative Scores With Qualitative Assessments

Organizations must also collect qualitative data to evaluate their TTX’s effectiveness. Consider, for example, using the Likert scale to assess customer satisfaction for a restaurant. In the same way that a low score would not, by itself, reveal why the customer was dissatisfied (e.g., poor food quality or poor service), exclusive reliance on the numeric values of the quantitative score would not provide an organization with the insight needed to understand why the TTXs may or may not have improved its preparedness. By directly linking and integrating the quantitative data with the qualitative data, evaluators obtain more accurate and comprehensive insight regarding effectiveness.

Qualitative assessments must focus on exercise objectives during the “hot wash” and subsequent participant feedback. While facilitators can ask “open-ended” questions during the hot wash, exercise participants should focus their immediate comments on their organization’s preparedness. Hot wash participants providing comments on organizational preparedness – strengths and areas for improvement – rather than on the exercise’s execution or logistics in written post-exercise questionnaires, enables the immediate discussion to focus on more important preparedness questions.

Effective exercise evaluation requires careful planning from the beginning of the exercise design phase and when observing and collecting data, including comparing exercise objectives to how participants performed during the exercise. For example, asking questions such as “How was exercise objective #1 accomplished?” will provide important data regarding improving the response and organizational preparedness for the exercise. To further the qualitative data collection process, evaluators should ask the following key questions:

- Were the participants exercised on the specific plan, policy, and procedure the organization intended to assess?

- Did the participants understand the specific plan, policy, and procedure discussed during the exercise?

- Did the participants understand how to execute the plan, policy, and procedure?

- Did the participants follow their organization’s plans, policies, and procedures, or were gaps identified (e.g., actions not stated in plans), indicating the need to reassess a particular plan, policy, or procedure?

- What were the consequences of the decisions made?

Responses to the above questions should help exercise evaluators reach several important conclusions about the TTX’s effectiveness. For example, suppose participants did not demonstrate an understanding of a policy, plan, or procedure during the TTX. In that case, evaluators may need to conduct a root-cause analysis to better understand why that happened. Using qualitative assessments as part of a root-cause analysis can provide key data for an after-action report and improvement plan. When compiling this information, however, evaluators must consider the direct relationship among several factors that can affect the evaluators’ conclusions about the data they collected, including:

- Whether there were well-considered and developed exercise goals and objectives;

- The quality of the data collected;

- Whether there were experienced and skilled exercise facilitators;

- Whether appropriate exercise participants were present; and

- Whether exercise participants were assured that the TTX was “no-fault” and “non-attributional” after-action report and improvement plan data collection would occur.

When participants receive “no-fault” and “non-attributional” assurances about the answers they will be providing to the TTX evaluation questions, better qualitative data will be collected because participants will have less reluctance to admit a lack of understanding, a shortfall in a policy, plan, or procedure, or the fact that the appropriate individuals and agencies did not participate. The collected data can then enable evaluators to reach conclusions about whether the TTX contributed to the following:

- Team building, agency coordination, and enhancing familiarity among response assets and leadership;

- Participants’ increased knowledge of their roles and responsibilities and how they would be applied during a particular scenario;

- Participants’ increased knowledge of others’ roles and responsibilities;

- Participants’ increased identification of any gaps in policies, plans, or procedures; and

- Participants’ increasing knowledge of potential threats, vulnerabilities, or consequences, if those subjects were covered during the exercise.

The collected qualitative information plays a significant role in evaluating organizational change and whether TTXs have improved the organization’s preparedness. However, separate briefings with exercise evaluators, controllers, and facilitators would produce the most complete and accurate assessment.

Testing Future Preparedness Efforts

Testing response capabilities in exercises prepares personnel and organizations for all types of threats, hazards, and incidents, and ensures that plans are current and effective. TTXs are a cost-effective way for the government, private companies, and non-government organizations to test their preparedness. Following a checklist to create a well-designed TTX will maximize an organization’s chances for a successful TTX. When a TTX is well-designed, engages participants, and is conducted effectively, participants’ written responses to post-exercise questionnaires can provide important indicators of whether the TTX improved organizational preparedness. Yet, no industry standard exists for evaluating this effectiveness over time.

There is a need for a new industry standard for a reliable, objective, and cost-effective way to evaluate TTX effectiveness. The new standard should be based on quantitative and qualitative data that is tied to exercise objectives and that assigns weighted values to the most important exercise factors to better understand the TTX’s impact on organizational preparedness. However, care must be taken regarding the scoring statements, exercise design, and delivery. Moreover, conducting TTXs alone is not enough to ensure organizational preparedness. When a comprehensive and integrated preparedness program has senior leaders’ support and the exercises are appropriately resourced, organizations can maximize the return on investment in their training investments and pursue multi-year exercise plans and priorities through effective program management.

Author note: Since 2012, one of the authors of this article has noted the lack of an industry standard for quantitative assessments of TTXs, which prompted him to develop a rubric that included various factors for analyzing and measuring exercise effectiveness. Based on their extensive exercise experience in both the government and the private sector, the authors of this article have further refined the rubric into what we call the XF ScoreTM. Building on and improving the eight questions included in the sample HSEEP Participant Feedback Form, the XF Score, along with integrated qualitative assessments, provides a practical, easy-to-use, and cost-effective method for organizations to evaluate the effectiveness of TTXs objectively and reliably. This approach could lead to a new industry standard that helps organizations maximize their return on investment and use their limited exercise budgets wisely to enhance organizational preparedness.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of any government department or agency or private sector organization. This article contains no classified, confidential, or otherwise sensitive government information. The authors wish to thank Holly Hardin, Christine Moore, Jessica Mielec, and Chris Norris for their prior review and comments, and Mart Stewart-Smith for his review, comments, and contributions, to an earlier draft of the article. Mr. Duda and Mr. Glick can be reached here.

John Duda

John R.Dudais thechief executive officerofSummit Exercises and Training LLC(SummitET®), a veteran-owned small business thatspecializes inprovidingproven full spectrum preparedness solutions to systematically address all threats and hazards through a wide-range of services.Mr. Duda has led and supported multiple domestic and international exercise and training programsfornumerousgovernment and non-government organizations.Mr. Duda has also co-authored a research study involving defense-based sensor technology and has been certified as asenior professionalin Human Resources and as a Business Continuity Professional. Prior to formingSummitET, Mr. Duda served many organizations including the U.S. Department of Energy/National Nuclear Security Administration, Publix Super Markets, and the Jacksonville Port Authority. Mr. Duda is also a member of the Advisory Board for the University of North Florida’s School for International Business and the cybersecurity and compliance company,RISCPoint.

- John Dudahttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/john-duda

Scott J. Glick

Scott J. Glick is vice president and general counsel for Summit Exercises and Training LLC (SummitET®), a veteran-owned small business that specializes in providing proven preparedness solutions to systematically address all threats, hazards, and incidents through a wide range of services, including planning, training, and exercises, as well as operational and policy support, for its government and private sector clients. He has nearly four decades of experience in law enforcement, counterterrorism, critical incident response, exercises, and emergency preparedness. He previously served as the director of preparedness and response and senior counsel in the National Security Division at the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), where he led DOJ’s national preparedness policy and planning efforts, including in regard to countering weapons of mass destruction (WMD), and where he provided substantial guidance to the FBI in the development of the WMDSG. He also investigated and prosecuted international terrorism cases as a federal prosecutor, and organized crime cases with as a state prosecutor in New York. This article contains no classified or confidential government or business information, and the views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of any government department or agency, or any private sector company.

- Scott J. Glickhttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/scott-j-glick

- Scott J. Glickhttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/scott-j-glick