The National Incident Management System includes unity of effort as one of its guiding principles. It is easy to spot in after-action reports when it is not in place on a large-scale incident. However, the opposite seems to be true for the Francis Scott Key Bridge Collapse response and recovery work in Baltimore, Maryland. Unity of effort has been apparent – from the bridge collapse and death of six workers on March 26, 2024, to the ongoing environmental and economic restoration of business in and around the port and channel.

Different Goals, Same Key Objectives

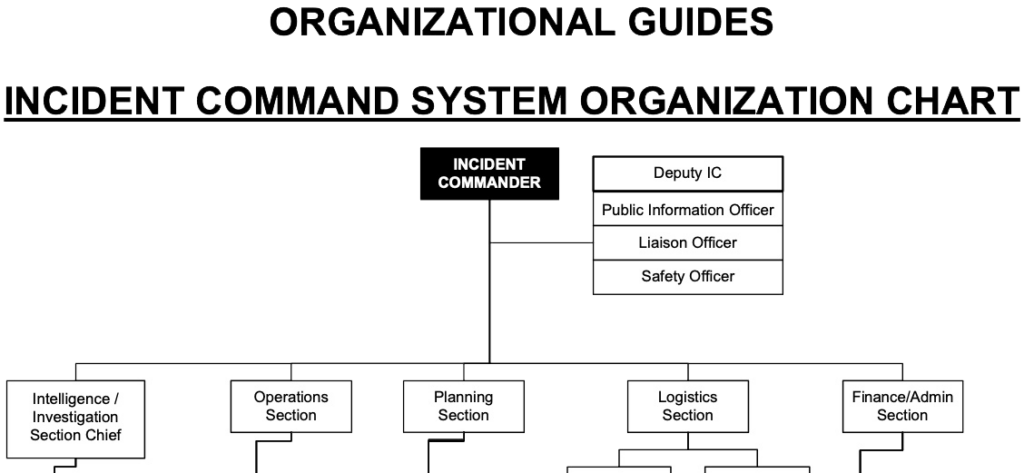

Incident command includes leading more than just a massive operations section. The general staff leads and the other elements of the command team (safety officer, liaison officers, and public information officer) were activated for this incident. The U.S. Coast Guard organizes using a general unity of effort model in its civilian support operations for disasters (see Figure 1) to work together while maintaining jurisdictional responsibilities and authority. An acronym the author uses as a mnemonic for organizing the command structure is IFLOPI (Incident Command, Finance and Administration, Logistics, Operations, Planning, and Intelligence).

The incident response to this bridge collapse undoubtedly includes varying objectives and competing agendas regarding who will ultimately face financial or other consequences. However, a commander’s intent often follows the priorities of life safety, incident stabilization, property and asset protection, environmental and economic restoration, and recovery and resiliency in the long term, which can be remembered with another one of the author’s mnemonics LIPER. The first part of this acronym – the LIP – originates in the fire service. This mnemonic can help command staff keep their priorities straight, which is especially important for complex incidents like the Key Bridge collapse. Unity of effort is critical in this scenario because moving piece A of the bridge might disturb piece B, which could damage the ship further or endanger divers below.

Incident Command

The incident command for the Key Bridge operation comprises a lead federal coordinating officer, a deputy coordinator, a safety officer, a public information officer leading a joint information center (or JIC), and several liaison officer positions. For example, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Weather Service’s Eastern Regional Operations Center supports the unified command with weather intelligence from its Bohemia, New York office. The JIC has produced almost daily reports, which anyone can subscribe to, and consolidated public-facing information on a unique open-source website: https://www.keybridgeresponse2024.com/. Other groups providing liaison support to unified command, as of this publication, include the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, National Transportation Safety Board, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Naval Sea Systems Command’s Supervisor of Salvage and Diving, Maryland Port Authority, National Resource Police, Baltimore City, Baltimore County, Anne Arundel County, Cyber Security & Information Security Agency, Maryland Emergency Management, Pipeline & Hazardous Material Safety Administration, Environmental Protection Agency, and Seaman’s Church.

Finance and Administration

Many personnel and expensive equipment resources from different agencies, departments, organizations, etc., are involved in this response and recovery operation. One significant difference between regular business or governmental management and emergency management is the idea of budgeted costs. A typical corporate or governmental project starts with a finite budget and builds capacity and results from there. In emergency management, it is the opposite. The required results and the capacity needed to get there are the key metrics or drivers – and then the tabulation, documentation, and quantification of expenses. Cost cannot and should not be a primary limiting factor when making decisions during a disaster response. The Key Bridge collapse response and recovery work is being funded by a combination of public and private funding, and does not qualify for Stafford Act funding via the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

Logistics

There is undoubtedly a unity of effort for logistical support for the bridge collapse incident. As with any large-scale event, logistical elements need unified coordination. This incident has land, water, and underwater transportation needs to bring the workforce back and forth to the scene and remove massive amounts of debris to an offsite location. For example, it takes unity of effort to organize the tenders that carry divers and investigators to the Dali. This effort also coordinates with engineers using advanced underwater light detection and radar (LIDAR) to map wreckage locations for fatality recovery, clear the channel for ship traffic, and support unique equipment to lift large bridge sections from the water onto barges. As of May 2024, the response has become primarily a logistics-led operation. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers estimates there were more than 50,000 tons (45,359 mt) of steel and concrete that collapsed into the Patapsco River.

Operations

Human remains recovery work missions have now ended. As of this publication, search teams have retrieved all six of the deceased bridge workers from the water. Announcements of this work in April and early May 2024 were posted in English and Spanish on the Key Bridge Response 2024 website. However, this incident dramatically impacted the immigrant and working-class groups as well as others in and around Baltimore, as recovery efforts ran concurrent with restoring portions of the channel, removing the underwater bridge parts, investigating the crash, recovering the (sometimes hazardous material) cargo containers that fell off the ship, and conducting other recovery phase work. In one unity-of-effort example, a diver working on debris removal had to change the mission after finding a vehicle underneath the wreckage. By May 9, 2024, the unified command authorized the use of explosives to help remove the remainder of the fallen bridge section that prevented the Dali from moving.

Planning

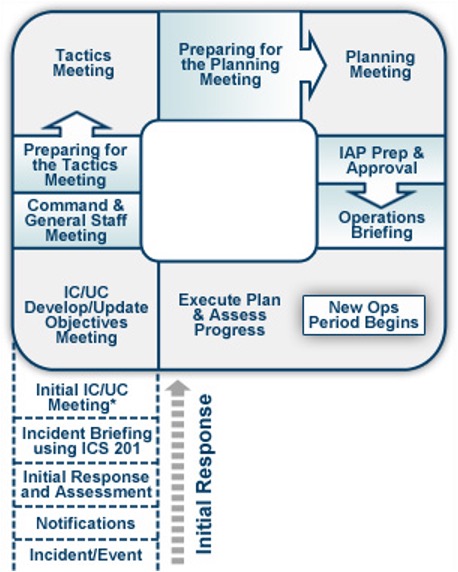

Planners must coordinate, collaborate, cooperate, and communicate with everyone involved in the operation for the next steps – tomorrow’s incident action plan and mission assignments. As noted earlier, the LIPER dictates priorities. It is the planners’ job to guide everyone through a common unified pattern of meetings, discussions, adjustments, etc., through the spiral of the “Operational O” at the recovery and debris removal point of this operation.

Priorities continually change over time, but unity of effort is necessary to accomplish any mission. For example, now that Dali has been refloated, recovery efforts will shift from relocation planning to other mission areas.

Intelligence and Investigation

According to personal communication between the author and the public information officer group of the response, the unified command for the Key Bridge collapse did not initially establish a separate grouping for intelligence and investigation. The unified command directly manages the intelligence, with different incident command systems (Federal Bureau of Investigation, National Transportation Safety Board, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, etc.) conducting the investigation leadership. Curating intelligence – and sharing it with the rest of the command and general staff, as needed – is required for this type of incident. Siloing intelligence has historically had downfalls in other incidents, including those that involved chemical spills, such as the Paulsboro, New Jersey train derailment in 2012. However, this operation is providing the public with a high degree of transparency of its curated intelligence on what the response is doing, how, and why. This also helps to quell misinformation and disinformation.

An Incident Response Still in Progress

As of publication, all the missing people have been recovered, debris is still being removed from the river, the Dali has yet to be relocated, and different depth channels from the open waterway to and from the Port of Baltimore are still being established. With all these missions, the Incident Command System is constantly being adjusted. From an investigative perspective, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is one of the groups that initially coordinated its independent investigation work on-scene, collaboratively through a liaison officer at the unified command team. When the NTSB was doing its on-scene work, they benefited from being part of the unified command.

Other continuing marine investigation activities are now being coordinated under the operations group, led by U.S. Coast Guard District 5, which covers Sector Maryland – National Capital Region. The U.S. Coast Guard is the federal on-scene coordinator for the unified command team. It certainly helps to have all the groups conducting investigations included in the unity of effort so that evidence is not destroyed, mishandled, etc., and that the overall workforce safety priorities on the Key Bridge collapse also included the safety of all of the various investigators who worked on this site.

The Key Bridge Response 2024’s unified command is continuing to provide information to the public via its previously noted website and media releases. According to its Community Information and Outreach page, “Through proactive outreach, inclusive dialogue, and collaborative efforts, the goal is to establish trust, foster understanding, and address the unique needs and concerns of impacted residents and communities.”

This article is the third in a series on the Key Bridge collapse:

Michael Prasad

Michael Prasad is a Certified Emergency Manager®, a senior research analyst at Barton Dunant – Emergency Management Training and Consulting, and the executive director of the Center for Emergency Management Intelligence Research. He researches and writes professionally on emergency management policies and procedures from a pracademic perspective. His first book Emergency Management Threats and Hazards: Water was published by CRC Press in September 2024, and his second book Rusty the Emergency Management Cat is now available on Amazon to assist emergency managers in communicating with families to help them alleviate disaster adverse impacts on children. He holds a B.B.A. from Ohio University and an M.A. in emergency and disaster management from American Public University. Views expressed may not necessarily represent the official position of any of these organizations.

- Michael Prasadhttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/michael-prasad

- Michael Prasadhttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/michael-prasad

- Michael Prasadhttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/michael-prasad

- Michael Prasadhttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/michael-prasad