Emergency management and crisis leadership demand more than technical skills and knowledge in today’s fast-paced and complex world. To better access information on demand, make appropriate decisions, and lead most effectively, it is essential to understand how the brain works. A critical cognitive skill set known as executive function (EF) is at the heart of effective decision-making in high-pressure situations.

Leaders with robust EF skills are at a distinct advantage. They are better equipped to make informed decisions under pressure and navigate the intricacies of contemporary organizational landscapes and global challenges. EF is especially critical in crisis management and high-stakes decision-making scenarios where clarity of thought and efficient action can be game-changers.

So, What Exactly Is Executive Function?

For years, the concept of EF has predominantly fallen under neuropsychology, clinical psychology, and psychiatry. Within these fields, knowledge of EF helps address various cognitive disorders and mental health conditions. It provides a framework for understanding how people plan, organize, strategize, remember instructions, and juggle multiple tasks – essentially, how to manage mental processes.

Fast forward, and EF is emerging from clinical settings into the broader spheres of general psychology, education, and leadership development conversations. This expansion is a testament to the universality and importance of understanding EF and how brains work in daily life. EF has become a cornerstone for developing teaching strategies and classroom accommodations in educational settings because these skills are vital for academic success and life-long learning and adaptation.

EF is an evolving field of study and definition. Understanding of EF will continue to evolve and expand, fueled by technological and scientific advances, such as functional MRIs and other imaging and measurement tools. Its importance and application may also grow. Although academics debate various components of EF, there is a consensus that EF comprises a set of skills essential for many aspects of cognitive and behavioral regulation involving multiple areas of the brain.

Core components of EF include:

- Inhibitory control – The ability to self-regulate and deliberately control impulsive responses or thoughts.

- Working memory – The capacity to retain and manipulate information, rapidly update that information with relevant information, and filter out anything irrelevant.

- Cognitive flexibility – Often referred to as shifting, cognitive flexibility involves planning, goal-direction, perspective-taking, and adapting to new information or unforeseen changes.

Multiple studies underscore the significance of these components in effective leadership, particularly in high-stress decision-making environments.

Come Again – In Plain Language Please (With a Dash of Neuroscience)!

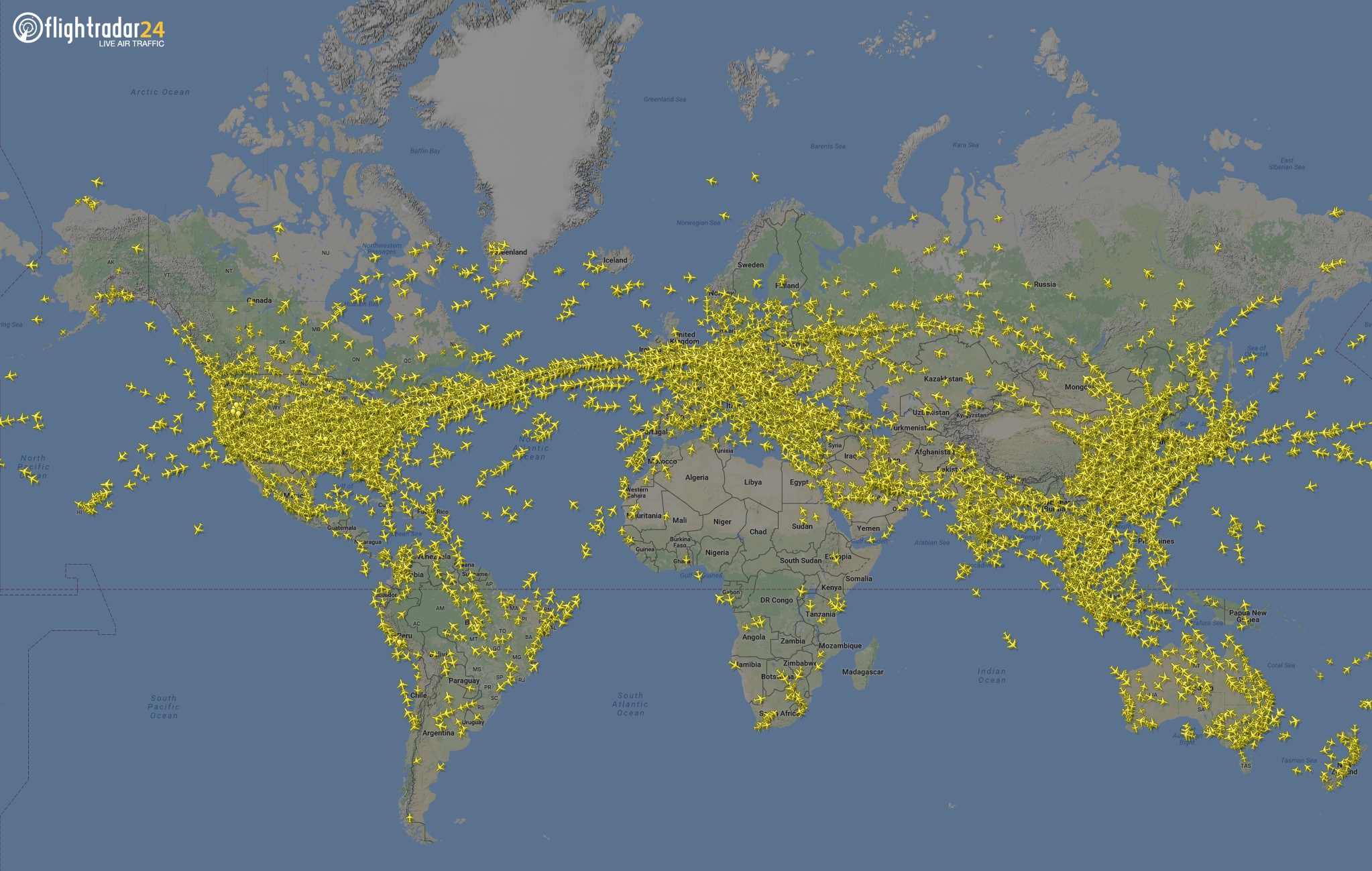

EF is like the brain’s air traffic control system. It acts as the brain’s command center, orchestrating thoughts, actions, and emotions to achieve goals.

The air traffic control system supports the coordination of a global network of aircraft. With precision timing to the second, it manages a complex series of 24/7 takeoffs, flights, and landings to ensure the safe and efficient movement of people and goods. Looking at a point-in-time Flight Map and knowing there are an average of 120,000 planes in the air each day, it appears as if airplanes are stacked on top of each other. Yet, air crashes and collisions are rare.

In the human brain, there are approximately 86 billion neurons. Since each neuron forms connections with others, there is the potential for more than a quadrillion (1,000 trillion) connections. According to another fun fact, information in the brain travels at a rate of about 268 miles (431 km) per hour. Airplanes travel a little faster than that, but comparatively, there are 120,000 planes in the air each day, compared to 86 billion neurons firing. A lot happens in the brain at any given moment, and the brain’s EF system has to manage that complex coordination and influx of information and direct mental resources at precise moments of need.

In the same way that air traffic controllers are carefully selected and trained to manage increasingly complex tasks, people can also train their brains to enhance EF capacity and capability. This is possible due to the brain’s remarkable ability to change, known as neuroplasticity.

Executive Function in Action

In an emergency, inhibition and control are essential to maintain focus amid the chaos with calm composure and leadership-driven focus.

Working memory allows for strategic planning and response, and helps the brain adapt, update, and filter out the irrelevant.

The ability to adapt, change, pivot, challenge biases, and re-think priorities that may keep people anchored and inflexible is core to cognitive flexibility.

Many emergency managers come from technical backgrounds – fire, law enforcement, tactical military, healthcare, etc. However, the more complex the emergency, the greater the need to go beyond technical skills and knowledge. There is the need to think and act differently. For example:

- Who else and what other perspectives do we need to draw in to understand?

- What initial instincts to put out the fire, secure the perimeter, or contain the disease do I need to tap down to think more globally?

Answering these questions requires a higher-order brain process. It involves stopping and recognizing that the most familiar lens may not be the one that most clearly sees the whole picture and the potential cascading impacts.

Building & Enhancing Executive Function Skills

EF does not develop in the moment of crisis. Instead, it comprises the skills, daily practices, and brain and organizational training that occur BEFORE the crisis. This preparedness allows people to rise to the occasion.

When under threat – perceived or real – survival instincts take over. Understanding this and knowing how the brain functions can get people back into the moment and prevent them from sinking to the lowest level of their training.

- Learn about the brain – Understand how to harness its power and limitations. Understand how behaviors are rooted in brain function. The brain weighs an average of 3 pounds (1.4 kg) but consumes 20% of the body’s energy. It is the supercomputer of supercomputers, and it resides entirely within you.

- Build emotional intelligence skills – It is not a fad or something people are born with – it is a set of skills that can be taught and learned. Vice Admiral Thad Allen (U.S. Coast Guard, Retired) stated in a 2021 Naval Post Graduate School keynote on “Managing Complex Disasters” that “The skills we need to teach to others are empathy, emotional intelligence, and collaboration as we expect emergency managers to step up in a more complex world.”

- Stress management, emotion regulation, and self-soothing – Stress can increase executive dysfunction, making stress more difficult to handle. Equip your toolbox and encourage others to do the same. Some examples are below, and there are numerous others. Learn what works best for each person:

- Deep, slow breathing exercise series: Breathe in for a count of 5, hold for 5, exhale for 8, and hold for 5;

- “Name it to tame it” emotion labeling; and

- The butterfly hug technique, which was developed by Lucina Artigas while working with Hurricane Pauline survivors in Acapulco, Mexico, in 1998.

- Build personal networks and phone a friend (or expert) – No person is an island or knows everything. Thinking you are, or have to be, will short-circuit the EF system. Include as much diversity in your circle as possible. During an emergency, especially in the midst of a novel event, people often need to be with someone to help think it through and re-focus.

- Mix up routines – Routines can make people operate on autopilot, like driving home and not remembering how you got there. Routines simplify life, but they can also dull cognitive skills when activities are not varied occasionally. Simple changes, such as taking a different route, trying a new food, adding a new exercise to a routine, or starting a meeting at a different time, can enhance cognitive flexibility. Small deviations from the norm help keep the brain engaged.

- Leverage everyday skill-building strategies:

- Slow time – Crises and emergencies and the immediacy of today’s varied media put additional pressure to work faster. This is not procrastination. Rather, a short pause can allow the brain to re-focus and get neurons firing in the same direction. Slowing time may mean a 5-minute break with a walk around the block, building, or floor or some deep breaths to pause and re-center on the goal.

- Set a clear mission and goal – This may be as simple as asking, “What is the goal now for the next 5 or 50 minutes?” Goal setting can help calm the noise and allow the brain to reconnect and reengage. EF needs a goal. When it is most overwhelming, a clear mission and goal can be unifying for the brain and others.

- Set a timer to stay focused – It is like giving the brain a mini goal. You can hit repeat or snooze on the digital timer again and again, but the knowledge the timer is on can help keep the brain on track.

What This Means for Today’s Professionals

This article is a call to action to hone these critical cognitive skills. For leaders and aspiring managers, consciously developing and enhancing EF skills can lead to more effective decision-making, improved problem-solving abilities, and a more strategic approach to challenges – even when those challenges are novel.

Navigating a world that requires and values adaptability, strategic thinking, and effective decision-making, the importance of EF cannot be overstated. Regardless of the role someone plays – a mentor shaping the mind and training the next generation of emergency managers or a leader steering an organization toward success – everyone can benefit from understanding and developing EF skills.

Kim Guevara

Kim Guevara, MA, is the founder and CEO of Mozaik Solutions. She has 25 years of experience in emergency management, homeland security, and development. She has provided services to all levels of government, the U.S. military, and the private and non-profit sectors. She is known for building and enhancing emergency and crisis management programs and stakeholder engagement. Her executive experience includes leadership for change management and business transformation initiatives to improve employee morale, talent recruitment, and retention. She has significant international experience in telemedicine and humanitarian development and led and supported initiatives and efforts in Southwest Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean. She is the co-creator of the Crisis Athlete™ program, which leverages a unique blend of neuroscience, emotional intelligence, performance coaching, sports and industrial/organizational psychology, and other disciplines to foster resilience and peak performance. She is a significant contributor and author of the groundbreaking study on the unique stressors and organizational challenges in emergency management published in the Journal of Emergency Management in October 2023.

- Kim Guevarahttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/kim-guevara