Increased focus on insider threats has resulted in greater attention to background screening and automated methods to assist the vetting process for initial and continued access to secure facilities and classified information. Recent technology applications can provide investigators with an ever-increasing variety of data for screening and continued vetting. Applying this model to homeland security and emergency management, however, presents broader cultural issues, including information privacy and interoperability.

Background screening refers to the process of checking for the presence or absence of specific information that would affect the candidate’s eligibility for the position. Vetting refers to the overall evaluation of the candidate’s behavior and temperament for initial and continued suitability for the position. Combining biometric-based and non-biometric searches into background screening processes has enabled one successful program to use the approach known as continuous evaluation (CE). The result is a significant reduction in cost and investigator effort, and more rapid notification of behavioral events that could jeopardize personnel or protected assets.

However rigorous an initial background screening check and vetting process may be for a new employee or contractor, the vast majority of screenings represent only a snapshot of the person’s past behavior at the moment the information is requested. Traditionally, public agencies and private employers have dealt with the inherent risks of this snapshot view by mandating a periodic reinvestigation. However, the screening information used for the vetting and evaluation process remains a snapshot. The limits of traditional background screening approaches can be dramatic and tragic. Attitudes and behaviors sometimes change either purposefully or due to factors outside people’s control, such as: radicalization; employee disillusionment; mental and emotional instability; substance abuse; financial stress; or purposeful infiltration. Therefore, the current background check system does not work because it introduces risk into the system through unmonitored periods of time.

During the timeframe between investigations a person can have documented contact with authorities that are not transmitted until the next snapshot reinvestigation. The Navy Yard shooting in September 2013 is an example where the subject had several potentially disqualifying encounters in the interval between the most recent snapshot screening and the date of the incident.

One solution is to shorten the interval between snapshots. However, this approach increases costs substantially and may not be practical because of the increased resource requirements placed on personnel who conduct the investigations. The current clearance program does not uniformly meet the current reinvestigation timeframe targets, much less, shorter ones. An alternative to the snapshot approach – known as continuous evaluation (CE) – is technologically available and has been discussed for several years in the Department of Defense, U.S. Office of Personnel Management, and intelligence environments. The CE approach allows for ongoing reviews of cleared people so their continued eligibility can be more easily monitored without the need for periodic reinvestigations.

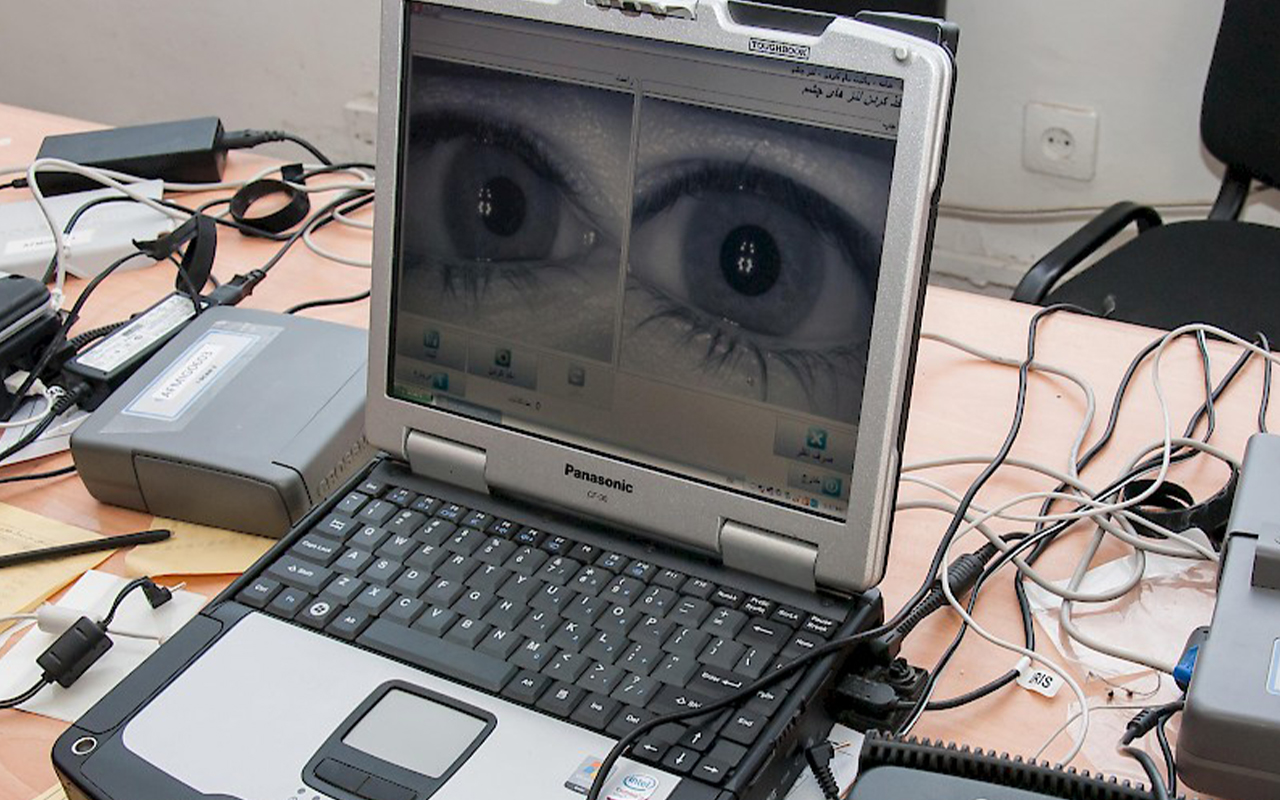

Importance of Biometric Identification for CE

The most efficient and reliable method of providing positive identity and for updating law enforcement information to the screening authority is based on biometric identity and the use of rap back technology. “Rap back” is a technology offered under the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Next Generation Identification (NGI) Rap Back Service that notifies authorized agencies and organizations when a person who holds a position of trust and has fingerprints on file within NGI is arrested or has criminal activity against those fingerprints. The technology and procedures are fully operational at both state and federal Criminal Justice Information Service (CJIS) authorities. Some of the benefits for both an initial and continuing evaluation include:

- Eliminating multiple identity matches (false positives) and missed matches (false negatives) compared to character-based searches;

- Returning criminal history record information under current, new, and former names and aliases;

- Uncovering identity theft and/or erroneous records; and

- Adjudicating rap back notifications, as with initial criminal history records, to determine if the event affects the individual’s suitability for the specific position held.

Another technology critical to CE is data matching, which involves comparing and matching identification fields in different sources of data to build a more complete profile of a person. Basic individual data matching uses name, date of birth, social security number, and possibly other data from a primary source to determine if a record in the primary database is listed in a secondary database. For CE, this matching is highly automated and is triggered by certain changes in either the primary or secondary database.

The accuracy and completeness of both data sources and tightness of matching criteria affect the quantity and quality of data-matching results. Adding identity data from a fingerprint-based request significantly improves subsequent data matching. Ultimately, having data matching combined with biometrics in a continuous evaluation process results in more accurate identification, and reduces overall costs associated with background checks – as demonstrated by an innovative program administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Successful Example of a CE Program With Biometrics

The National Background Check Program (NBCP) is a biometric-based CE screening program best practice. The NBCP, a federally supported grant program out of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, helps state agencies develop more robust methods to screen employees of certain healthcare organizations. CNA, as the technical assistance provider, designed a CE approach that has been implemented in 20 states since 2010. The solution has used a combination of biometrics and data matching to conduct initial screenings and provide CE on several million people. This program is a useful example of the power and challenges of integrating data and technologies while adhering to myriad state and federal privacy and data security requirements. The development of this program and the experience of implementing it in diverse state regulatory and technical environments can inform homeland security policy makers and developers in biometrics and data integration.

The NBCP, under the Affordable Care Act Section 6201, requires participating states to conduct fingerprint-based state and federal criminal record checks, search relevant state and federal databases, and use techniques, such as rap back, to eliminate duplicate fingerprinting. A single state agency is required to manage the program and to receive, investigate, and notify people and their employers whenever eligibility changes due to rap back. NBCP’s biometric-based CE screening program incorporates the following key features to ensure that the requirements result in effective, efficient, economical, and equitable screening and eligibility decisions:

- Collection and retention of fingerprints for all applicants – Fingerprints are collected electronically for each new applicant into the affected industry in the state. All fingerprints are retained by the state CJIS agency and (optionally) by the FBI, and immediately subscribed to rap back. Under rap back, civil applicant fingerprints are retained at the state or federal CJIS repository as long as certain conditions are met related to the reason for the fingerprints. The retained prints are matched against all subsequent incoming criminal fingerprints. If a match occurs, the requestor (who submitted the civil applicant prints initially) is notified of the criminal CJIS event, again under certain rules governing which events will trigger a notification. If the requestor no longer has a legitimate interest in the person, the fingerprint notification service is no longer available to that requestor.

- Centralized screening information and eligibility decision – A single agency at the state level maintains the background screening response information, performs the investigation to determine if any information is disqualifying for the position, and maintains the eligibility decision. The agency also establishes an independent authority and process for appeals (challenging the correctness of the decision or information used) and/or waivers (permission to work, in spite of disqualifying information, on the basis of individual circumstances).

- Rap back – The state agency (eligibility authority) is notified by electronic transmission whenever a CJIS event is recorded for the applicant on file. The new information is automatically matched to the person’s information on file with the state agency. The information is investigated, and the person’s eligibility is updated in accordance with the state agency’s eligibility criteria as needed. All current employers of record get a secure notice whenever the person’s eligibility status changes.

The practice of using fingerprints and rap back to provide the basis for continuous evaluation of criminal justice involvement has been slow, and not all NBCP states are participating. Cultural and political resistance has prevented the passage of needed authorizing legislation in seven NBCP states. For the states that do use mandatory fingerprinting and rap back, a substantial number of subsequent notifications (“hits”) have been received and adjudicated. As of 31 December 2016, four NBCP grantee states had received 93,492 rap back notifications. Not all rap back notifications result in a loss of eligibility. In fact, only 35,185 were subsequently deemed ineligible to work based on state program decisions and individual case review.

Continuous evaluation pertaining to noncriminal justice information events (e.g., mental health, professional misconduct) requires a non-biometric approach. Relevant noncriminal justice information data is generated and maintained by a plethora of state and federal agencies. NBCP, for example, supports data matching from a variety of sources that contain information affecting a person’s eligibility for healthcare employment, including:

- State health professional license and misconduct records – To be eligible, people must have the required license or certificate, and must not have an active finding or other license action due to certain types of misconduct;

- State sex offender and adult abuse records – Individuals on these lists are not eligible for employment; and

- Federal Medicaid List of Excluded Individuals and Entities – Individuals on this list are prohibited from performing Medicaid-covered services.

Current technology makes near-real-time data matching on registries not only possible, but nearly instantaneous and transparent to the investigator. The NBCP and its technology platform can match multiple large databases interactively when an applicant is entered into the primary database, and it can conduct background matching in different ways whenever a secondary database is updated. As a result, the NBCP platform performs a daily automated all-on-all data-matching routine, known as “registry recheck.” Where unique identifiers are available, the match returns virtually no false positives, similar to the biometric-based rap back. In cases where unique identifiers are not available, the data-matching routine is adjusted to minimize the number of potential matches to be resolved.

The expansion of the data matching has also been more constrained by organizational issues than by technology or cost. Even in such a homogenous and limited scope of data and usage, cultural issues arise; typically because some state agencies choose to maintain tight control, and do not allow public access to their abuse registries.

A challenge for automated registry rechecks is that state-maintained database content, quality, currency, and technology for access vary widely by state. In addition, effective access and data matching often require agency agreements, technology upgrades, and data integrity improvements regarding the secondary databases. This challenge is magnified with the NBCP provision that participants must search the health licensing and professional misconduct files of all other states where the person may have lived or worked. Rather than relying on people to provide an accurate list of states and for the investigating agency to search them all, the NBCP now supports a secure data-matching approach for the healthcare eligibility programs in several NBCP states.

A common web service automatically calls and returns the most current results from 11 states’ professional misconduct registries for each individual applicant in any of the 11 states. The web service approach allows states to retain control of their data while making the latest data instantly available to users of the common service. During 2016, five states processed 163,039 applications through this web service. A total of 140 matches were returned identifying people who were ineligible to work.

A notable achievement of this biometric-based CE screening program is that it greatly reduces the costs because of the reduced time and resources needed to conduct repeated background checks. One NBCP state, for example, reported a cost savings of more than $10 million in six years as a result of the program.

Applicability to Preparedness & Homeland Security

Homeland security has many needs for background checks of wide-ranging complexity. Currently, there are different background check requirements based on varying metrics for federal government employees, state and local government employees, or contractors in different fields such as transportation and emergency management.

Implementing a CE process in even a segment of the broad and diverse homeland security field will require a combination of technology and organizational and political collaboration. The technology for CE is available now and will continue to enable more effective, efficient, and economical solutions as biometric data collection and large-scale data processing improve. The bigger challenge to implementing any meaningful CE process in the homeland security and emergency management field will be the cultural, privacy, and political issues, which are much larger than those faced in the smaller and less complex NBCP example.

Emergency management alone has physical credentialing requirements, a vast array of access authorizations, and complex needs for interoperability at the local, state, and federal levels, as well as many other cultural constraints. A monolithic CE process is not desirable or practical, but a collaborative sharing of source data can facilitate customized CE programs in different segments. Whether a background check is needed for a clearance for access to sensitive information, suitability determination for fitness to perform a function, or a credential to allow a qualified responder access to a disaster site, each process can benefit from continuous evaluation because it is critical to know if each person is still trustworthy.

A bill introduced into the House of Representatives (H.R. 876) on 6 February 2017 to amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 would require biometric identification technologies and continuous vetting through the FBI’s Rap Back Service for airport workers with a goal of rapidly detecting and mitigating insider threats to aviation security. Bills like this one will become more common across the various homeland security fields (e.g., land and sea ports of entry, federally declared disasters) because there is need for continuous evaluation, and the biometric technology exists to make it more effective and efficient.

Progress toward biometric-based and non-biometric CE will be determined by organizational and political processes, not technology. One strategy for consideration is to establish a pilot project in one or two closely related functions in the homeland security credentialing and access practice. Such a pilot project could identify solutions to cultural issues, clarify performance metrics, and provide an indication of the returns on investment for the approach. The NBCP experience has produced operational, multi-state continuous evaluation programs in the public sector across more than 20 states, each with their own legislative requirements, engaging multiple state agencies within each state, and with interfaces into the FBI NGI and other federal offender and exclusion lists. This program can provide some best practices and inform future efforts to move toward a biometric-based CE program in homeland security and emergency management.

Ernest Baumann

Ernest Baumann is a senior advisor for the National Background Check Program at CNA, a nonprofit research and analysis organization located in Arlington, Virginia. He is an expert in fingerprint-based background checks for health care licensing and employment and has experience in IT solutions architecture, business and workflow analysis, data integration, and project management.

- This author does not have any more posts.

Delilah Barton

Delilah Barton is an associate director of CNA’s Safety and Security division. Her expertise is in emergency management and homeland security. She currently serves as the CNA program director for the National Background Check Program, coordinating technical assistance to 26 states enrolled in the program.

- This author does not have any more posts.