The nature and scope of the emergency management field can be defined in a variety of ways. An all-hazards definition of emergency management encompasses some essential homeland security concerns. A conceptual framework then helps bring together an understanding of the challenges facing those in the emergency management and homeland security fields when an all-hazards definition of emergency management is used.

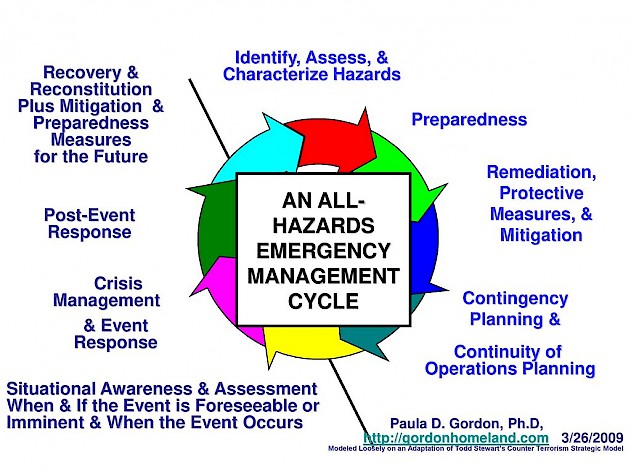

Emergency management can be applied to emergencies of any possible origin – emergencies that can impact the lives of hundreds, thousands, or millions of individuals. However, elements of the emergency management cycle, as they tend to be defined, may not be well-known to people outside the field of emergency management (e.g., within the newer field of homeland security). In addition, those in homeland security may have educational and professional backgrounds that differ notably from those in emergency management. Public service experience and hands-on involvement in addressing emergency situations may also differ substantially. With disparate backgrounds, experiences, and public service orientation among those in emergency management and homeland security, the All Hazards Emergency Management Cycle (see Fig. 1) – including elements of preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery – provides a way of looking at emergency management while accommodating and integrating key elements of concern that are shared by those in both fields.

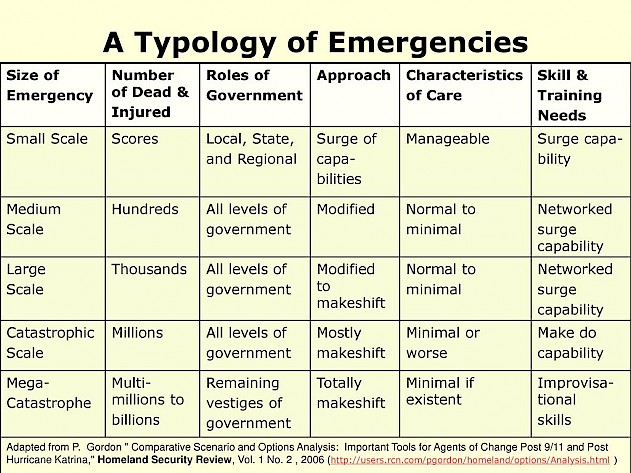

A Typology of Emergencies of Differing Levels of Severity

Developed in the early 1980s, the Typology of Emergencies (see Table 1) was created to illustrate the numerous possibilities that exist when considering emergencies of differing levels of severity. It was developed in part from a perceived need to help decision makers exercise realistic expectations when considering a full range of possible scenarios, including worst case scenarios. The typology was developed to help decision makers expand their thinking when assessing possible worst scenarios along a variety of parameters. This offers a way to assess these scenarios in far more realistic ways than had been the case in the past.

An Impact Scale’s Applicability to All-Hazards Emergency Management

The Washington, DC Year 2000 Group (WDCY2K) was a networking organization composed of members from the public and private sectors – including government, business, nonprofit organizations, and academia – with interests in Y2K-related challenges. In 1998, the WDCY2K created the Y2K Impact Scale as a survey instrument to learn the different ways in which its membership was assessing the possible impacts of Y2K.

Originally called the Homeland Security Impact Scale, the All Hazards Impact Scale – ranked 0-10 – is a conceptual tool adapted from the Y2K Impact Scale for educators, researchers, policymakers, and practitioners:

0. No real impact on national security, economic security, or personal security

1. Local impact in areas directly affected

2. Significant impact in some areas that were not directly affected

3. Significant market adjustment (20%) and drop; some business and industries destabilized; some bankruptcies, including increasing number of personal bankruptcies and bankruptcies of small businesses, and waning of consumer confidence

4. Economic slowdown spreads; rise in unemployment and underemployment; accompanied by possible isolated disruptive incidents and acts, increase in hunger and homelessness

5. Cascading impacts including mild recession; isolated supply problems; isolated infrastructure problems; accompanied by possible increase in disruptive incidents and acts, continuing societal impacts

6. Moderate to strong recession or increased market volatility; regional supply problems; regional infrastructure problems; accompanied by possible increase in disruptive incidents and acts, worsening societal impacts

7. Spreading supply problems and infrastructure problems; accompanied by possible increase in disruptive incidents and acts, worsening societal impacts, and major challenges posed to elected and non-elected public officials

8. Depression; increased supply problems; elements of infrastructure crippled; accompanied by likely increase in disruptive incidents and acts; worsening societal impacts; and national and global markets severely impacted

9. Widespread supply problems; infrastructure verging on collapse with both national and global consequences; worsening economic and societal impacts, accompanied by likely widespread disruptions

10. Possible unraveling of the social fabric, nationally and globally, jeopardizing the ability of governments to govern and keep the peace

This adapted scale provides a common frame of reference for recognizing, identifying, analyzing, and discussing key factors that can be considered by those tasked with formulating and implementing policy. The All Hazards Impact Scale can be used in various ways:

- To help decision makers, planners, analysts, and practitioners air differences in perspectives concerning the impact that an emergency has had or may likely have.

- To serve as a common framework for discussing different perceptions of a current or potential event’s impact.

- To help clarify differences in perspective that key actors and stakeholders may have concerning an event.

- To help those in decision-making roles arrive at a consensus as to the seriousness and extent of the impacts of an event.

- To understand, assess, and manage specific events, challenges, and possibilities.

Response Collaborations

The differences in experience and professional backgrounds between those in the fields of emergency management and homeland security were especially notable after 9/11. Those who became involved in homeland security efforts at that time did not tend to come from the field of emergency management. Owing to the differences in backgrounds, a gap became apparent between those in the then separate fields. These differences still exist to some extent today within the multi-discipline, multi-jurisdictional efforts required to tackle modern emergencies and disasters.

When persons of different backgrounds work on the same disaster, conflicting missions and goals can make it hard to come to a consensus. Having a clear framework helps.

When persons with such different backgrounds find themselves working on the same disaster, it can be hard to arrive at a common understanding of the mission and goals, not to mention arrive at a consensus concerning the steps that might be needed to address an emergency, particularly one of unprecedented scope. Such differences were particularly apparent when FEMA ceased being an independent agency and became part of the Department of Homeland Security. For example, the conflict that ensued both before and following Hurricane Katrina is particularly well documented in a series of articles that appeared in the Washington Post in December 2005.

The Typology of Emergencies, the All Hazards Emergency Management Cycle, and the All Hazards Impact Scale can be helpful tools in emergency management and homeland security. They can help individuals and organizations in various ways:

- To develop multidimensional perspectives concerning emergencies of differing levels of severity and impact;

- To provide a deeper understanding of the differences between catastrophes and lesser emergencies, the various plans that need to be in place, and the numerous actions that need to be taken;

- To help deepen an understanding of scenarios that have unfolded as well as spur imagination for scenarios that could unfold;

- To aid those in decision-making roles to act more proactively and realistically than in the past, particularly regarding catastrophic and other unprecedented events.

A framework that accomplishes these tasks for disasters of any size is important, but most importantly when it comes to catastrophic events that involve significant failure of major elements of the critical infrastructure. Understanding the nuances between disasters, jurisdictional plans, and necessary actions is critical. After all, emergency management and homeland security should be complementary to one another and not fundamentally at odds.

Expanding Course Content to Cover Multi-Tiered Disasters

Following are some topics involving emerging issues and realities that should be incorporated into the content of a curriculum that features an all hazards approach to emergency management:

- The variations of the terrorist and anarchist mentalities

- The differences in pre- and post- 9/11 perspectives concerning the nature and implications of the terrorist and anarchist threats

- Pandemics – including flu, Ebola, Zika virus, and coronavirus

- Drug abuse, addiction, and the opioid crisis as a national public health disaster

- Humanitarian disasters – including homeless encampments

- Catastrophic hurricanes, tornadoes, and floods

- The New Madrid Fault and the San Andreas Fault

- The triggering of earthquake faults by man-made factors

- The implications of the Japan earthquake and Fukushima Disaster for nuclear power plants in the seismically sensitive zones in the U.S.

- Wildfires caused by drought, environmental degradation and neglect, and/or other man-made causes

- Climate changes

- Changes in the gravitation of the Earth and magnetic North

- Solar storm activity

- Asteroid and meteorite activity

- Electromagnetic pulse (EMP)

- Cyber-related threats and challenges, including lessons learned and unlearned from Y2K

- Blackouts and cascading infrastructure impacts

- GPS and satellite interference, natural and man-made

- Impact-type approaches that focus on prevention, preparedness, mitigation, resilience, sustainability, and recovery

- Implementation of a culture of preparedness

- Preparedness and planning for worst case catastrophic events

How narrowly or broadly emergency management educators define the nature and scope of emergency management will shape the future of the field, the roles that professionals in the field assume, and the competencies they develop. Educators are in roles of responsibility for helping prepare those who aspire to careers in emergency management and public service become as effective as they can be in those roles. Educators also can do much to advance the expertise and knowledge of those who have already accrued considerable experience in the field. This article provides an overview of one perspective on what an all-hazards approach to emergency management can encompass.

Paula Gordon

Paula D. Gordon, Ph.D. is an educator, writer, and consultant, based in Washington, D.C. She has had responsibilities in the federal government for coordinating interagency and intergovernmental efforts and directing or taking part in projects in various fields, including drug abuse prevention and emergency management and homeland security. These assignments have included the National Institute for Mental Health, the National Science Foundation, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the Environmental Protection Agency. In addition, she has served as an adjunct professor and practitioner faculty member for The George Washington University and Johns Hopkins University, among other institutions. She is currently developing and teaching online courses for Auburn University Outreach on topics including the drug crisis as a national public health disaster, the effects and impacts of marijuana use and legalization, and emergency management and homeland security. Her websites include the following: http://GordonDrugAbusePrevention.com, http://GordonPublicAdministration.com, and http://GordonHomeland.com (e-mail: pgordon@starpower.net).

- Paula Gordonhttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/paula-gordon