Numerous incidents occur every day in the United States, from simple or frequent events like automobile accidents, train derailments, and severe weather, to catastrophic or infrequent events like the 9/11 terrorist attacks, hurricanes Harvey and Maria, and the Keystone pipeline leak to name just a few. By examining factors related to the incident and factors related to a specific entity, information needs and resource requirements can be better aligned to create operational resilience during any incident.

The number of participants and resources required to respond and recover, and the complexity of their roles and responsibilities, are significantly greater and more difficult for a catastrophic incident than for a simple incident. As complexity increases, there is a corresponding need for enhanced resilience, much of which can be achieved through increased agility. Understanding the information needs across different scale incidents provide insight into how various agencies and jurisdictions can better coordinate their resources.

Categorizing Small- to Large-Scale Incidents

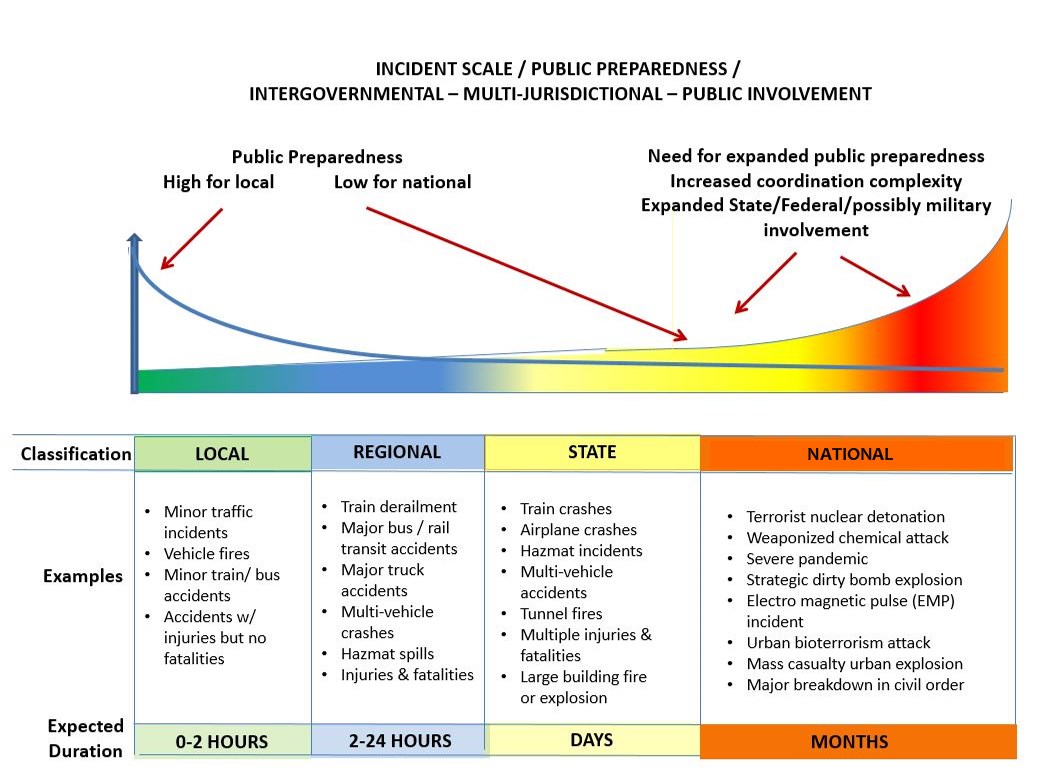

The incident-preparedness scale graphic (Figure 1) shows the interconnected nature of large-scale events. As they escalate from local to national, coordination complexity typically varies and increasing complexity emerges. The duration of an event is another significant factor. Viewing incidents at local, regional, state, and national levels recognizes that the degree of coordination required across various independent agencies and jurisdictions increases when moving from left to right (local to national). Participants must come together, coordinate, and adapt quickly as events occur, escalate, and impose cascading effects across infrastructure sectors.

Figure 1. Incident Public-Preparedness Scale (Source: J. Contestabile, used with permission; previously published in CIO Leadership for Public Safety Communications: Emerging Trends and Practices, 2012).

The vertical scale depicts the level of public preparedness typically in place. For example, the number of first responders involved and public affected in a “local” incident is relatively small and public preparedness is high. The scene of the incident is usually cleared in less than two hours, the disruption is minimal, and there is no cascading impact on adjacent infrastructure.

However, some events rapidly grow into something more significant than initially expected. For example, a local incident may involve a vehicle transporting hazardous waste, which then spills during the event. More units and agencies would become involved, and the incident scale would increase to “regional,” requiring more time to resolve (2–24 hours). During a high-traffic period, roadway congestion may cause motorists to seek alternative routes, causing “ripple effects” that could cascade to other roadways and mass transportation systems.

Some events expand into a “statewide” impact, whereas others start immediately as a state concern. The threat of a hurricane would normally start as a statewide threat, take place over a period of days, impact overlapping local, regional, and state systems, and require activation of state and local emergency operations centers. Multiple agencies are involved as the complexity increases, requiring multiagency coordination and increased information sharing, possibly including the National Guard to supplement local and regional resources.

Finally, some events are classified as national incidents because they grow into a national disaster (e.g., disease epidemics, pandemics, wildfires, major flooding), or are so catastrophic (e.g., 9/11) that the president immediately declares them national disasters or homeland defense events. The impact of this type of event extends across multiple infrastructure sectors and touches multiple domains (air, land, sea, and cyber). Supply chain interruptions can extend for months, in geographic areas far beyond those states immediately affected. Events of this magnitude typically result in a federal disaster declaration, triggering Federal Emergency Management Agency participation, activation of the Stafford Act, and potential support from the National Guard Bureau and the U.S. Northern Command. If the disaster has a terrorism nexus, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, elements of the Department of Homeland Security, and the intelligence community would likely be involved.

Determining the Effects of Incident Scale on the Agency

Private-sector companies and agencies in the public or not-for-profit sector are typically best able to manage incidents that are local in scale. These events occur most frequently, so agencies and organizations typically have considerable experience in managing the event, and the entity’s resources (e.g., personnel, equipment) tend to be aligned with the challenges that incidents of this scale present. Incidents of a regional, statewide, or national scale, however, happen less frequently and have broader impact across many companies, agencies, jurisdictions, and networks such as power, water, communications, and transportation.

Although the effect of large-scale incidents can have broader impact, the impact on any one company or agency may not necessarily be greater. The actual impact to a particular entity is related to its “connectedness” to that incident. The greater the connection – either physically or virtually – the greater the likelihood is of a significant impact. A strong physical connection to an incident may be due either to the incident occurring on a company or agency’s property or in close proximity, or reliance on a network, such as power, water, communications, or transportation for its operations. A virtual connection to an incident may be related to information technology or cyber assets, a contractual relationship to other entities involved in the incident, or the supply chain of which the entity is a part.

Thus, an on-premise explosion at a chemical manufacturer’s plant would establish a strong physical connection to the incident; whereas, a labor strike at an out-of-state contracted partner’s site would establish a virtual connection as a key supplier of material to the manufacturing process. Each would affect the entity to varying degrees.

Coping With Large-Scale Incidents

For an agency to successfully manage any incident, it must align the “tools” it has at its disposal to meet the challenges of the event. In a speech delivered by James Champy, independent consultant, author, and Harvard Business School research fellow, on 8 March 2013 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, those core tools were described as “people, processes, and technologies” (PPT). These PPTs must be integrated and aligned to accomplish basic work on a day-to-day basis. Many of these same tools are available to provide the capability to manage any incident. Thus, successfully managing large-scale incidents requires aligning PPTs to provide the requisite capability for the situation(s) presented by the incident.

It is not likely that a single entity would have every capability required to manage a large-scale incident because of funding constraints. Some needed resources may lie outside the entity’s control. For example, a company that transports chemicals would likely be prepared to respond to a small, localized, on-premises spill of a few gallons. But for an off-premises spill of several hundred gallons into a stream, contracted resources would likely be needed and external agencies notified. If the spill involves hazardous chemicals, evacuation may be required; this is usually the responsibility of fire or law enforcement agencies, which are likewise outside the company’s control.

To enhance resilience, a facility must determine what capabilities are needed to plan for, respond to, and recover from incidents beyond localized events and how much to invest in such preparedness, given the relatively infrequent nature of these large-scale incidents. This determination can only be made after assessing the relative risks, the likelihood of various large-scale scenarios occurring, and the possible impact(s).

In addition to having the capability to manage an incident, responders must be able to apply and adjust those capabilities in a rapidly evolving situation. The dynamic nature of unfolding incidents requires a certain organizational agility to be effective. Although agencies and organizations try to anticipate likely emergency events and plan accordingly, the reality is that every event is different in some respects from the scenarios used for planning. As such, flexibility and agility are needed to respond successfully. Agility in this sense incorporates the ideas of flexibility, balance, adaptability, and necessary coordination.

Agility is in large measure dependent on awareness of the incident. That is, operators must first discern that an incident has occurred and then have ongoing, accurate, awareness of unfolding or cascading events to take appropriate action. These are necessary conditions to remain effective as the incident changes over time – from response to recovery phases.

Defining Critical Success Factors for Large-Scale Incidents

Although many factors influence resilience as incident scale increases, a few factors have been identified thus far. It may be useful to think of this matter as a “ledger,” whereby certain factors are associated with the incident on the one side and factors associated with the agency on the other (see Table 1). The incident factors are stressors affecting the entity, whereas the entity factors are useful coping mechanisms. Table 1 lists parameters that define the incident as well as the tools the agency has to address the challenges presented by the incident.

| Incident-Related Factors | Entity-Related Factors |

|---|---|

Scale:

| Capabilities:

|

Connectedness:

| Awareness:

|

Agility:

|

Following are some questions to consider for incident-related factors:

- What scenarios does the entity want to prepare for?

- What are the various types of events experienced in the past?

- Are the designed scenarios sufficiently challenging? Would they likely challenge the whole agency?

- Has the entity considered a “worst-case” scenario? Has it exercised “out-of-the-box” thinking?

- How will the entity know an incident has occurred? Will this awareness remain if normal communications are disrupted?

- How connected is the entity to each scenario?

- Are there scenarios that occur both on premises as well as off premises?

- Can the entity discern impacts from the off-premises scenario (as these may not be obvious)?

- Considering each of the critical external inputs of power, communication, water, and transportation, how does the disruption of each affect the entity?

- What are the supply-chain impacts of each scenario? Are there unintended effects or consequences that will affect the entity? How will the entity know?

- How or when will contracted resources be accessed? What guarantees are there that the resource will be available?

Following are some questions to consider for entity-related factors:

- Does the entity have the requisite staff with the necessary skills to manage this scenario? Will they be available when needed?

- How will staff be contacted/activated during this scenario? Is there a policy/protocol/concept of operations addressing this?

- Do staff members have the requisite training and equipment to manage this scenario?

- What provisions have been made for the families of key staff?

- How/when will management be notified in this scenario? What methods will be used? Are there alternative methods should the usual be unavailable?

- Are there “workarounds” for a loss of the external inputs of power, water, transportation, and communication?

- Can the entity still function (albeit at a reduced state) in the face of the loss of these inputs? If not, does the entity “fail gracefully”? What steps must be taken to “shut down” the entity? Conversely, what steps must be taken to “start up” the entity?

- What are the trigger points at which the entity must make key decisions? Are there values/measures of performance for those triggers that can be utilized in a concept of operations? Is there a technological tool utilized?

- Does the scenario create vulnerability in the entity’s cyber posture? How will systems continue to operate with potential staff shortages and reduced power? Are certain IT staff designated as “key” and required to report?

- How will management remain aware of the current situation during the course of the scenario? During the recovery phase? Is there a technological tool utilized?

- What is the plan for releasing information to employees? To the public? Is social media involved in that process?

- With what external stakeholders – for example, fire, police, emergency management, suppliers, customers – must the entity coordinate? When? By what methods?

- When does the entity determine the need for mutual aid? Who makes that decision? What is the process for doing so? How would it be done with reduced communications capability?

Consideration of the above scenarios and questions should reveal the entity’s shortcomings, which include but are not limited to the following:

- Lack of policies and procedures

- Incomplete concept of operations

- Lack of staff with the requisite skills

- Lack of training and exercising

- Contractual shortfalls

- Communications gaps

- Technological issues

- Notification/coordination gaps

- Supply chain vulnerabilities

- Cybersecurity issues

- Lack of situational awareness

- Areas of limited flexibility

For each of the above, a corrective action plan can be developed to strengthen the entity’s posture and increase its resilience. Through effective oversight and governance, additional remedies can be implemented to improve preparedness, response, and recovery activities.

Recommendations

Two recommendations for improving operational resilience were provided by Rogier Woltjer et al. in their presentation An Overview of Agility and Resilience at the Resilience Engineering Symposium, 22–25 June 2015, Lisbon, Portugal:

First, understand the nature of the incident for which to be prepared. Typically, the focus would be on regional/statewide/national events as, presumably, sufficient capabilities already exist to manage local events. Gaining this understanding would involve scenario exploration and an examination of that entity’s incident response history. It also requires some consideration of worst-case scenarios. In each scenario, understand the connectedness of the agency to the incident. Examine physical and virtual connections and dependencies.

Second, understand the nature of the entity’s capabilities to plan for, mitigate, respond to, and recover from the identified scenarios. This would include how the agency would become aware that an incident may have occurred. It would also involve an examination of various business processes and technological systems as well as staff skill sets that could/should be brought to bear. Also, understand the entity’s ability to be agile, which includes the capability to provide notifications, establish and work within incident command structures, mobilize resources, and call for mutual aid.

Certainly, there is much to be researched and learned to understand just what it means to be “resilient.”

This article is based in part on the Resilience Engineering Association’s ongoing body of work, which was originally inspired by Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts by Eric Hollnagel, David Woods, and Nancy Leveson in 2006. Points of view or opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Johns Hopkins University–Applied Physics Lab.

John Contestabile

John Contestabile is the program manager for emergency response systems for the Johns Hopkins University/Applied Physics Lab. He joined the Lab in July 2009, after retiring from the State of Maryland Department of Transportation (MDOT), where he was acting assistant secretary for administration responsible for, among others, emergency management and homeland security. In addition, he was named acting deputy homeland security advisor by Governor Robert Ehrlich and later the director of the Maryland State Communications Interoperability Program (MSCIP), reporting to the superintendent of the Maryland State Police, by Governor Martin O’Malley. He is also a member of the Preparedness Leadership Council International.

- John Contestabilehttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/john-contestabile

- John Contestabilehttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/john-contestabile

- John Contestabilehttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/john-contestabile

Richard Waddell

Richard “DJ” Waddell is a principal staff systems analyst at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. He has extensive experience developing and managing technology solutions and is currently focusing on homeland protection projects on the technology needs of state and local first responders and emergency managers. He is the founding director of the National Criminal Justice Technology Research, Test and Evaluation Center. The Center is funded by the Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice, under Award #2013-MU-CX-K111.

- This author does not have any more posts.