The nation’s public health community has many parallels with the overall goals, basic concepts, models, and operational modes of the U.S. emergency management community. Using a broad spectrum of highly effective organizational and science-based tools, the public health and emergency management disciplines strive to protect the public from what is a rapidly growing spectrum of emergencies, disasters, and maladies. Both communities are multidisciplinary in their scientific bases (but public health is an older profession). Nonetheless, and despite their many common values and operational characteristics, members of the two communities have not always collaborated as smoothly and effectively as they probably should have in preparing for and responding to a number of mass emergencies.

The leading U.S. federal agencies – the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) for public health and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for emergency management – work closely together and, except for a few instances, can point to continually improved results in meeting every disaster. The recognition that every disaster has at least some harmful health consequences and almost any public health problem can quickly evolve into a disaster drives this increasingly important and frequently exercised partnership.

Standards & Capabilities

Each of the two professions has its own set of high standards. Emergency management, for example, has the Emergency Management Accreditation Program (EMAP), which assesses and accredits state and local jurisdictions, as well as higher education institutions that voluntarily undergo the process; more than half of all states and numerous local jurisdictions are now fully accredited. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1600 – a voluntary guide for all public, private, and nonprofit organizations in the fields of emergency management and business continuity – is a similar and widely used organization across many disciplines. Both have received special recognition from the American National Standards Institute.

In 2011, to help continue and expand the nation’s public health capabilities, the CDC published Public Health Preparedness Capabilities: National Standards for State and Local Planning, which provides a practical guide for state and local jurisdictions to organize their work, plan their priorities, and decide what capabilities and resources they must have to build and/or sustain their mission. The capabilities guide also helps to ensure that federal preparedness funds go to the priority areas most in need within individual jurisdictions.

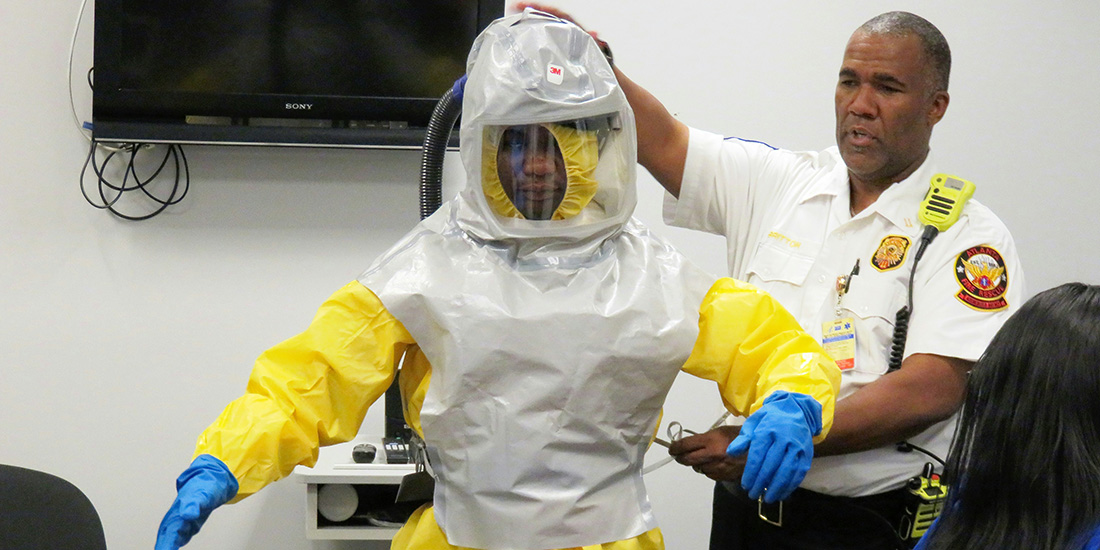

The public health capabilities standards guide encompasses, but is not limited to, the following: community preparedness and recovery, emergency operations coordination, emergency public information and warning, fatality management, information sharing, mass care, medical countermeasure dispensing, medical material management and distribution, medical surge, non-pharmaceutical interventions, public health laboratory testing, public health surveillance and epidemiological investigation, responder safety and health, and volunteer management.

The emergency management capabilities called for under EMAP and NFPA 1600 include the following: program management, administration and finance, laws and authorities, hazard identification, risk assessment, consequence analysis, hazard mitigation, prevention, operational planning, incident management, resource management, logistics, mutual aid, communications and warning, operations and procedures, facilities, training, exercises, evaluations, corrective action, crisis communications, and public education and information.

Other Core Components: Learning Centers & Training Opportunities

In August 2010, the CDC established a new iteration of the agency’s Preparedness and Emergency Response Learning Centers (PERLCs), building on the program’s successes and focusing on measurable results. Although the number of learning centers decreased from 27 to 14, the 14 centers remaining not only reach a collectively larger population but also provide more and better training.

Compensating for this reduction, the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act of 2006 authorized the CDC to establish a number of preparedness research centers – officially designated as Preparedness and Emergency Response Research Centers (PERRCs) – around the country. Combined, these nine research centers and 14 learning centers jointly produce widely used training materials for local, state, and federal officials – and, by doing so, create new, better, and longer lasting partnerships between and among all of the agencies involved. In one example, the PERRCs collaborate closely and effectively with law enforcement and public safety agencies, school systems, courts, and organizations serving vulnerable populations in order to continue to develop even more effective preparedness and emergency response processes.

At the state, tribal, and local levels, emergency management and public health mirror that national partnership even more closely through their emergency management departments or offices and the public health divisions of state and local health departments. Through the FEMA Higher Education Program, there are more than 275 colleges and universities offering degree and certificate programs in this field, many of which include courses in both emergency management and public health. Also, the FEMA Emergency Management Institute and the CDC offer room and online courses dealing with public health issues.

Real-Life Examples & Resources

The federal government is not alone in its efforts. The private sector also is helping considerably on a continuing basis. For example, the National Emergency Management Association (NEMA), which is composed of all state and territorial emergency managers, joined with the Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC) to host a webinar in the spring of 2013 focused on the umbrella topic “EMAC Planning in Support of Mississippi Public Health and Medical Response and Recovery Operations.” The principal speaker was James Craig, director for health and protection at the Mississippi State Department of Health; another high-level state official, Thomas McAllister, director of the Office of Response at the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency, introduced Craig. The webinar: (a) focused on the value of relationships between emergency management and public health/medical officials, especially regarding EMAC planning; (b) stressed the value of developing Mission Ready Packages (MRPs) to support planning for public health/medical responses; and (c) highlighted many of the medical resources that Mississippi now has at its disposal, the state’s own experiences in disasters, and the building of effective regional relationships and EMAC planning efforts.

Many other states also are involved in robust joint work on emergency management and public health missions. Following are a few examples:

- Oregon’s Center for Public Health Practice provides programs effective for communicable disease control and public health emergencies – including acute and communicable disease prevention, immunization, and health security, preparedness, and response – and works closely with county public health departments as well as local and tribal emergency services staffs.

- Oregon also has developed a health security preparedness and response program that encompasses such topics as: emergency alert systems for public health and healthcare staff; emergency risk communications toolkits; public health hazard-risk assessments; the state’s crisis-care guidelines; bioterrorism; strategic national stockpile resources; and strategic work plans.

- New York’s Department of Health has an overarching slogan – AWARE, PREPARE – and sponsors a broad spectrum of outreach and partnership programs throughout the state.

The true test of health emergency preparedness planning, of course, is how, and how well, healthcare professionals in private practice, hospitals, or emergency medical services (EMS) respond to and recover from a disaster. New York Health’s website is packed with emergency preparedness fact sheets, tools, and other instructional and educational resources specifically written for healthcare professionals. These resources can optimize local responses to the public health emergencies, whatever their causes, but specifically include: biological, chemical, and radiological emergencies; hospital/EMS preparedness; and maternal and child-health providers. New York also sponsors a ServNY registry of healthcare and mental health professionals who are willing to volunteer during an emergency or major disaster.

Many additional resources are available to help emergency managers and public health officials collaborate more often and more effectively. Some examples of those resources include:

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR)

- Oregon Coalition of Local Health Officials (CLHO), Preparedness Committee

- Social Media For Emergency Management (#SMEM)

- CDC Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication (CERC)

- National Public Health Information Coalition (NPHIC)

- Oregon’s Public Health Law in Emergencies

- The Portland, Oregon, Cities Readiness Initiative: Preparing Together Discussion Guide and Toolkit

Kay C. Goss

Kay Goss has been the president of World Disaster Management since 2012. She is the former senior assistant to two state governors, coordinating fire service, emergency management, emergency medical services, public safety, and law enforcement for 12 years. She then served as the associate Federal Emergency Management Agency director for National Preparedness, Training, Higher Education, Exercises, and International Partnerships (presidential appointee, U.S. Senate confirmed unanimously). She was a private-sector government contractor for 12 years at the Texas firm Electronic Data Systems as a senior emergency manager and homeland security advisor and SRA International’s director of emergency management services. She is a senior fellow at the National Academy for Public Administration and serves as a nonprofit leader on the board of advisors for DRONERESPONDERS International and for the Institute for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Management. She has also been a graduate professor of emergency management at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas for 16 years, Istanbul Technical University for 12 years, the MPA Programs Metropolitan College of New York for five years, and George Mason University. She has been a certified emergency manager for 27 years; Arkansas Tech University Emergency Management and Homeland Security Program Advisory Council Member for 28 years; Metropolitan College of New York Emergency Management and Homeland Security Advisory Council for 15 years; and founder of the FEMA Higher Education Program, established in 1994.

- Kay C. Gosshttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/kay-c-goss

- Kay C. Gosshttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/kay-c-goss

- Kay C. Gosshttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/kay-c-goss

- Kay C. Gosshttps://www.domesticpreparedness.com/author/kay-c-goss